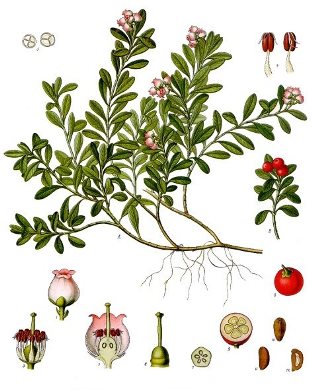

Aberia (Dovyalis) caffra (Keiapfel): "South Africa. The fruits are of a golden-yellow color, about the size of a small apple. They are used by the natives for making a preserve and are so exceedingly acid when fresh that the Dutch settlers prepare them for their tables, as a pickle, without vinegar."

Abronia latifolia (Gelbe Sand-Verbene): "Seashore of Oregon and California. The root is stout and fusiform, often several feet long. The Chinook Indians eat it."

Abrus precatorius (Paternostererbse): "A plant common within the tropics in the Old World, principally upon the shores. The beauty of the seeds, their use as beads and for necklaces, and their nourishing qualities, have combined to scatter the plant. The seeds are used in Egypt as a pulse, but Don says they are the hardest and most indigestible of all the pea tribe. Brandis says the root is a poor substitute for licorice."

Abutilon esculentum: "Brazil. The Brazilians eat the corolla of this native plant cooked as a vegetable."

Abutilon indicum (Indische Samtpappel): "Brazil. The Brazilians eat the corolla of this native plant cooked as a vegetable."

Acacia (Vachellia) abyssinica: "Abyssinia. Hildebrant mentions that gum is collected from this species."

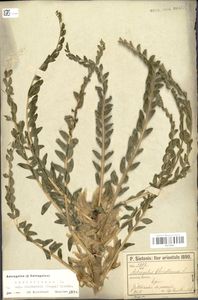

Acacia (Vachellia) nilotica (Arabische Gummi-Akazie): "North and central Africa and Southwest Asia. It furnishes a gum arable of superior quality. The bark, in times of scarcity, is ground and mixed with flour in India, and the gum, mixed with the seeds of sesame, is an article of food with the natives. The gum serves for nourishment, says Humboldt,9 to several African tribes in their passages through the dessert. In Barbary, the tree is called atteleh."

Acacia (Vachellia) bidwillii: "Australia. The roots of young trees are roasted for food after peeling."

Acacia (Senegalia) catechu (Gerber-Akazie): "East Indies. Furnishes catechu, which is chiefly used for chewing in India as an ingredient of the packet of betel leaf."

Acacia concinna: "Tropical Asia. The leaves are acid and are used in cookery by the natives of India as a substitute for tamarinds. It is the fei-tsau-tau of the Chinese. The beans are about one-half to three-fourths inch in diameter and are edible after roasting."

Acacia decora: "Australia. The gum is gathered and eaten by Queensland natives."

Acacia decurrens (Schwarze Akazie): "Australia. It yields a gum not dissimilar to gum arable."

Acacia ehrenbergiana: "Desert regions of Libya, Nubia, Dongola. It yields a gum arabic."

Acacia farnesiana: "Tropics. This species is cultivated all over India and is indigenous in America, from New Orleans, Texas and Mexico, to Buenos Aires and Chile, and is sometimes cultivated. It exudes a gum which is collected in Sind. The flowers distil a delicious perfume."

Acacia ferruginea: "India. The bark steeped in "jaggery water"—fresh, sweet sap from any of several palms — is distilled as an intoxicating liquor. It is very astringent."

Acacia flexicaulis: "Texas. The thick, woody pods contain round seeds the size of peas which, when boiled, are palatable and nutritious."

Acacia glaucophylla: "Tropical Africa. This species furnishes gum arabic."

Acacia (Vachellia) gummifera: "North Africa. It yields gum arabic in northern Africa."

Acacia homalophylla: "This species yields gum in Australia."

Acacia (Vachellia) horrida (Schreckliche Akazie): "South Africa. This is the dornboom plant which exudes a good kind of gum."

Acacia (Vachellia) leucophloea: "Southern. India. The bark is largely used in the preparation of spirit from sugar and palm-juice, and it is also used in times of scarcity, ground and mixed with flour. The pods are used as a vegetable, and the seeds are ground and mixed with flour."

Acacia longifolia: "Australia. The Tasmanians roast the pods and eat the starchy seeds."

Acacia (Vachellia) pallidifolia: "Australia. The roots of the young trees are roasted and eaten."

Acacia penninervis: "Australia. This species yields gum gonate, or gonatic, in Senegal."

Acacia (Senegalia) senegal (Gummiarabikumbaum): "Old World tropics. The tree forms vast forests in Senegambia. It is called nebul by the natives and furnishes gum arable."

Acacia brachystachya: "Southern Nubia and Abyssinia. The gum of this tree is extensively collected in the region between the Blue Nile and the upper Atbara. It is called taleh, talha or kakul."

Acacia suaveolens: "Australia. The aromatic leaves are used in infusions as teas."

Acacia (Vachellia) tortilis: "Arabia, Nubia and the desert of Libya and Dongola. It furnishes the best of gum arabic."

Acaena anserinifolia (Becherblütiges Garten-Stachelnüsschen): "Australia. The leaves are used as a tea by the natives of the Middle Island in New Zealand, according to Lyall. It is the piri-piri of the natives."

Acanthorhiza (Cryosophila) aculeata: "Mexico. The pulp of the fruit is of a peculiar, delicate, spongy consistence and is pure white and shining on the outside. The juice has a peculiar, penetrating, sweet flavor, is abundant, and is obviously well suited for making palm-wine. The fruit is'oblong about one inch in longest diameter. It is grown in Trinidad."

Acanthosicyos horridus (Nara): "Tropics of Africa. The fruit grows on a bush from four to five feet high, without leaves and with opposite thorns. It has a coriaceous rind, rough with prickles, is about 15-18 inches around and inside resembles a melon as to seed and pulp. When ripe it has a luscious sub-acid taste. The bushes grow on little knolls of sand. It is described, however, by Anderson as a creeper which produces a kind of prickly gourd about the size of a Swede turnip and of delicious flavor. It constitutes for several months of the year the chief food of the natives, and the seeds are dried and preserved for winter consumption."

Acer dasycarpum (Silber-Ahorn): "North America. The sap will make sugar of good quality but less in quantity than the sugar maple. Sugar is made from this species, says Loudon, in districts where the tree abounds, but the produce is not above half that obtained from the sap of the sugar maple."

Acer platanoides (Spitzahorn): "Europe and the Orient. From the sap, sugar has been made in Norway, Sweden and in Lithuania."

Acer pseudo-platanus (Bergahorn): "Europe and the Orient. In England, children suck the wings of the growing keys for the sake of obtaining the sweet exudation that is upon them. In the western Highlands and some parts of the Continent, the sap is fermented into wine, the trees being first tapped when just coming into leaf. From the sap, sugar may be made but not in remunerative quantities."

Acer rubrum (Rot-Ahorn): "North America. The French Canadians make sugar from the sap which they call plaine, but the product is not more than half that obtained from the sugar maple. In Maine, sugar is often made from the sap."

Acer saccharinum (Zucker-Ahorn): "North America. This large, handsome tree must be included among cultivated food plants, as in some sections of New England groves are protected and transplanted for the use of the tree to furnish sugar. The tree is found from 48° north in Canada, to the mountains in Georgia and from Nova Scotia to Arkansas and the Rocky Mountains. The sap from the trees growing in maple orchards may give as an average one pound of sugar to four gallons of sap, and a single tree may furnish four or five pounds, although extreme yields have been put as high as thirty-three pounds from a single tree. The manufacture of sugar from the sap of the maple was known to the Indians, for Jefferys, 1760, says that in Canada "this tree affords great quantities of a cooling and wholesome liquor from which they make a sort of sugar," and Jonathan Carver, in 1784, says the Nandowessies Indians of the West consume the sugar which they have extracted from the maple tree." In 1870, the Winnebagoes and Chippewas are said often to sell to the Northwest Fur Company fifteen thousand pounds of sugar a year. The sugar season among the Indians is a sort of carnival, and boiling candy and pouring it out on the snow to cool is the pastime of the children."

Acer tataricum (Tataren-Ahorn): "Orient. The Calmucks, after depriving the seeds of their wings, boil them in water and afterwards use them for food, mixed with milk and butter."

Achillea millefolium (Schafgarbe): "Europe, Asia and America. In some parts of Sweden, yarrow is said to be employed as a substitute for hops in the preparation of beer, to which it is supposed to add an intoxicating effect."

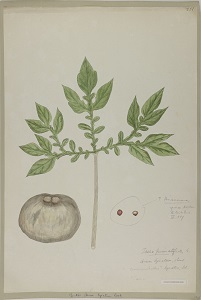

Achras (Manilkara) zapota (Breiapfelbaum): "South America. This is a tree found wild in the forests of Venezuela and the Antilles. It has for a long time been introduced into the gardens of the West Indies and South America but has been recently carried to Mauritius, to Java, to the Philippines, and to the continent of India. The sapodilla bears a round berry covered with a rough, brown coat, hard at first, but becoming soft when kept a few days to mellow. The berry is about the size of a small apple and has from 6 to 12 cells with several seeds in each, surrounded by a pulp which in color, consistence, and taste somewhat resembles the pear but is sweeter. The fruit, when treeripe, is so full of milk that little rills or veins appear quite through the pulp, which is so acerb that the fruit cannot be eaten until it is as rotten as medlars. In India, Firminger says of its fruit: " a more luscious, cool and agreeable fruit is not to be met with in any country in the world; " and Brandis says: "one of the most pleasant fruits known when completely ripe." It is grown in gardens in Bengal."

Achyranthes bidentata: "Tropical Asia. The seeds were used as food during a famine in Rajputana, India. Bread made from the seeds was very good. This was considered the best of all substitutes for the usual cereals."

Aciphylla glacialis: "Australia. This species is utilized as an alimentary root."

Aconitum lycoctonum (Wolfs-Eisenhut): "Middle and northern Europe. The root is collected in Lapland and boiled for food. This species, says Masters in the Treasury of Botany, does not possess such virulent properties as others."

Aconitum napellus (Blauer Eisenhut): "Northern temperate regions. Cultivated in gardens for its flowers. A narcotic poison, aconite, is the product of this species and the plant is given by the Shakers of America as a medicinal herb. In Kunawar, however, the tubers are eaten as a tonic."

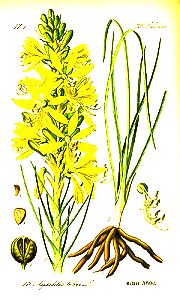

Acorus calamus (Kalmus): "Northern temperate regions. The rhizomes are used by confectioners as a candy, by perfumers in the preparation of aromatic vinegar, by rectifiers to improve the flavor of gin and to give a peculiar taste to certain varieties of beer. In Europe and America, the rhizomes are sometimes cut into slices and candied or otherwise made into a sweetmeat. These rhizomes are to be seen for sale on the street corners of Boston and are frequently chewed to sweeten the breath. In France it is in cultivation as an ornamental water plant."

Acorus gramineus (Zwerg-Kalmus): "Japan. The root of this species is said to possess a stronger and more pleasant taste and smell than that of A. calamus. It is sometimes cultivated in gardens."

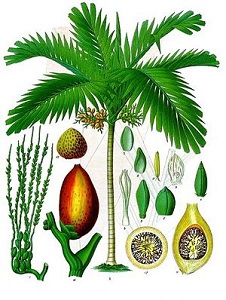

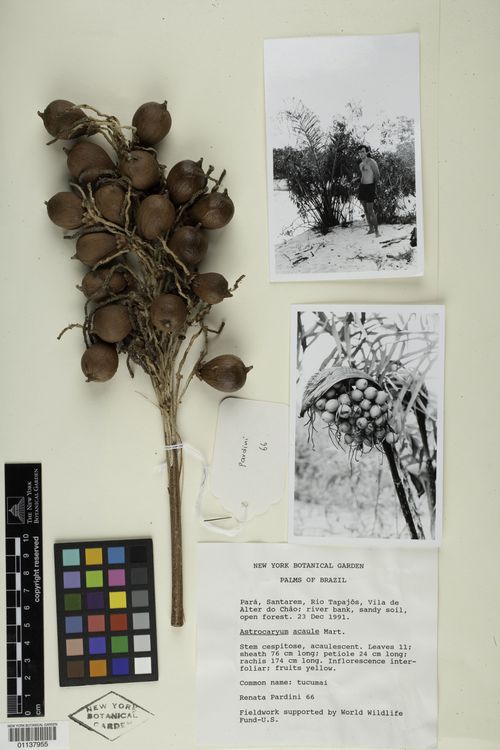

Acrocomia lasiospatha (Macauba-Palme): "West Indies and Brazil. Its fruit is the size of an apricot, globular and of a greenish-olive color, with a thin layer of firm, edible pulp of an orange color covering the nut, and, though oily and bitter, is much esteemed and eagerly sought after by the natives. This is probably the macaw tree of Wafer."

Acrocomia mexicana (Coyoli-Palme): "Mexico. The fruit, in Mexico, is eaten by the inhabitants but is not much esteemed."

Acronychia laurifolia (Jambol): "Tropics of Asia. The black, juicy, sweetish-acid fruit is an esculent. In Cochin China the young leaves are put in salads. They have the smell of cumin and are not unpleasant. In Ceylon the berries are called jambol."

Actinidia callosa: "Japan and Manchuria. This vine is common in all the valleys of Yesso and extends to central Nippon. It is vigorous in growth and fruits abundantly. The fruit is an oblong, greenish berry about one inch in length; the pulp is of uniform texture, seeds minute and skin thin. When fully ripe it possesses a very delicate flavor."

Actinidia polygama (Silberrebe): "Northern Japan. This is somewhat less desirable than A. callosa, as it fruits less abundantly and the vine is not so rich in foliage."

Adansonia digitata (Baobab): "East Indies. This tree has been found in Senegal and Abyssinia, as well as on the west coast of Africa, extending to Angola and thence across the country to Lake Ngami. It is cultivated in many of the warm parts of the world. Mollien, in his Travels, states that to the negroes, the Baobab is perhaps the most valuable of vegetables. Its leaves are used for leaven and its bark for cordage and thread. In Senegal, the negroes use the pounded bark and the leaves as we do pepper and salt. Hooker says the leaves are eaten with other food and are considered cooling and useful in restraining excessive perspiration. The fruit is much used by the natives of Sierra Leone. It contains a farinaceous pulp full of seeds, which tastes like gingerbread and has a pleasant acid flavor. Brandis says it is used for preparing an acid beverage. Monteiro says the leaves are good to eat boiled as a vegetable and the seeds are, in Angola, pounded and made into meal for food in times of scarcity; the substance in which they are imbedded is also edible but strongly and agreeably acid."

Adansonia gregorii (Australischer Baobab): "Northern Australia. The pulp of its fruit has an agreeable, acid taste like cream of tartar and is peculiarly refreshing in the sultry climates where the tree is found."

Adenanthera abrosperma: "Australia. The seeds are roasted in the coals and the kernels are eaten."

Adenanthera pavonina (Condoribaum): "One of the largest trees of tropical eastern Asia. The seeds are eaten by the common people. It has been introduced into the West Indies and various parts of South America."

Adenophora communis (Lilienblättrige Becherglocke): "Eastern Europe. The root is thick and esculent."

Adiantum capillus-veneris (Venushaarfarn): "Northern temperate climates. In the Isles of Arran, off the Galway coast of Britain, the inhabitants collect the fronds of this fern, dry them and use them as a substitute for tea."

Aeginetia indica: "Tropics of Asia. An annual, leafless, parasitic herb, growing on the roots of various grasses in India and the Indian Archipelago. Prepared with sugar and nutmeg, it is there eaten as an antiscorbutic."

Aegle marmelos (Belbaum): "East Indies. The Bengal quince is held in great veneration by the Hindus. It is sacred to Siva whose worship cannot be accomplished without its leaves. It is incumbent on all Hindus to cultivate and cherish this tree and it is sacrilegious to up-root or cut it down. The Hindoo who expires under a bela tree expects to obtain immediate salvation. 6 The tenacious pulp of the fruit is used in India for sherbet and to form a conserve. Roxburgh observes that the fruit when ripe is delicious to the taste and exquisitely fragrant. Horsfield says it is considered by the Javanese to be very astringent in quality. The Bengal quince is grown in some of the gardens of Cairo. The perfumed pulp within the ligneous husk makes excellent marmalade. The orange-like fruit is very palatable and possesses aperient qualities."

Aegopodium podagraria (Geißfuß): "Europe and adjoining Asia. Lightfoot says the young leaves are eaten in the spring in Sweden and Switzerland as greens. It is mentioned by Gerarde. In France it is an inmate of the flower garden, especially a variety with variegated leaves."

Aerva lanata: "Tropical Africa and Arabia. According to Grant, this plant is used on the Upper Nile as a pot-herb."

Aesculus californica (Kalifornische Rosskastanie): "A low-spreading tree of the Pacific Coast of the United States. The chestnuts are made into a gruel or soup by the western Indians. The Indians of California pulverize the nut, extract the bitterness by washing with water and form the residue into a cake to be used as food."

Aesculus hippocastanum (Gewöhnliche Rosskastanie): "Turkey. The common horse-chestnut is cultivated for ornament but never for the purpose of a food supply. It is now known to be a native of Greece or the Balkan Mountains. Pickering says it was made known in 1557; Brandis, that it was cultivated in Vienna in 1576; and Emerson, that it was introduced into the gardens of France in 1615 from Constantinople. John Robinson says that it was known in England about 1580. It was introduced to northeast America, says Pickering, by European colonists. The seeds are bitter and in their ordinary condition inedible but have been used, says Balfour, as a substitute for coffee."

Aesculus indica (Indische Rosskastanie): "Himalayas. A lofty tree of the Himalaya Mountains called kunour or pangla. In times of scarcity, the seeds are used as food, ground and mixed with flour after steeping in water."

Aesculus parviflora (Strauch- Rosskastanie): "Southern states of America. The fruit, according to Browne, may be eaten boiled or roasted as a chestnut."

Afzelia africana (Afrikanische Mahagoni): "African tropics. A portion of the seed is edible."

Afzelia quanzensis: "Upper Nile. The young purple-tinted leaves are eaten as a spinach."

Agapetes saligna: "East Indies. The leaves are used as a substitute for tea by the natives of Sikkim."

Agave americana (Hundertjährige Agave): "Tropical America. The first mention of the agave is by Peter Martyr, contemporary with Columbus, who, speaking of what is probably now Yucatan, says: " They say the fyrst inhabitants lyved contented with the roots of Dates and magueans, which is an herbe much lyke unto that which is commonly called sengrem or orpin." The species of agave, called by the natives maguey, grows luxuriantly over the table-lands of Mexico and the neighboring borders and are so useful to the people that Prescott calls the plant the " miracle of nature." From the leaves, a paper resembling the ancient papyrus was manufactured by the Aztecs; the tough fibres of the leaf afforded thread of which coarse stuffs and strong cords were made; the leaf, when washed and dried, is employed by the Indians for smoking like tobacco but being sweet and gummy chokes the pipe; an extract of the leaves is made into balls which lather with water like soap; the thorns on the leaf serve for pins and needles; the dried flower-stems constitute a thatch impervious to water; about Quito, the flower-stem is sweet, subacid, readily ferments and forms a wine called pulque of which immense quantities are consumed now as in more ancient times; from thispulque is distilled an ardent, not disagreeable but singularly deleterious spirit known asvino mescal. The crown of the flower-stem, charred to blackness and mingled with water, forms a black paint which is used by the Apaches to paint their faces; a fine spirit is prepared from the roasted heart by the Papajos and Apaches; the bulbs, or central portion, partly in and partly above the ground are rich in saccharine matter and are the size of a cabbage or sometimes a bushel basket and when roasted are sweet and are used by the Indians as food. Hodge, writing of Arizona, pronounces the bulbs delicious. Bartlett5 mentions their use by the Apaches, the Pimas, the Coco Maricopas and the Dieguenos Tubis.

The agave was in cultivation in the gardens of Italy in 1586 and Clusius saw it in Spain a little after this time. It is now to be found generally in tropical countries. The variety which furnishes sisal hemp was introduced into Florida in 1838 and in 1855 there was a plantation of 50 acres at Key West."

Agave parryi: "New Mexico and northern Arizona. This plant constitutes one of the staple foods of the Apaches. When properly prepared, it is saccharine, palatable and wholesome, mildly acid, laxative and antiscorbutic."

Agave utahensis: "staple foods of the Apaches. When properly prepared, it is saccharine, palatable and wholesome, mildly acid, laxative and antiscorbutic. A. utahensis Engelm. UTAH ALOE. Utah and Arizona. The bulb of the root is considered a great delicacy by the Indians, who roast and prepare it for food which is said to be sweet and delicious."

Agave wislizeni: "Mexico. The young stems when they shoot out in the spring are tender and sweet and are eaten with great relish by the Mexicans and Indians."

Aglaia edulis: "Fiji Islands and the East Indies. The natives eat the aril which surrounds the seed and call it gumi. The fruit is edible, having a watery, cooling, pleasant pulp. The aril is large, succulent and edible."

Aglaia odorata: "China. Firminger says this plant never fruits in Bengal. The flowers are bright yellow, of the size and form of a pin head and are delightfully fragrant. Fortune says it is the lan-hwa u yu-chu-lan of China and that the flowers are used for scenting tea. Smith says it is thesan-yeh-lan of China, that the flowers are used for scenting tea and that the tender leaves are eaten as a vegetable."

Agrimonia eupatoria (Gewöhnlicher Odermennig): "North temperate regions. The dried leaves are used by country people as a sort of tea but probably only for medicinal qualities."

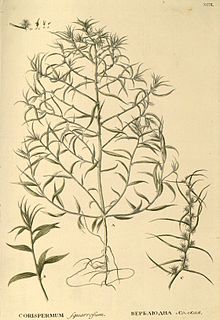

Agriophyllum gobicum: "Siberia. The seeds are used as food."

Agropyron repens (Kriech-Quecke): "Temperate regions. This is a troublesome weed in many situations yet Withering states that bread has been made from its roots in times of want."

Ailanthus glandulosa (Chinesischer Götterbaum): "China. Smith says that the leaves are used to feed silkworms and, in times of scarcity, are used as a vegetable."

Akebia lobata: "Japan. The fruits of the wild vines are regularly gathered and marketed in season."

Akebia quinata (Fingerblättrige Akebie): "China. The fruit is of variable size but is usually three or four inches long and two inches in diameter. The pulp is a homogeneous, yellowish-green mass containing 40 to 50 black, oblong seeds. It has a pleasant sweetish, though somewhat insipid taste."

Alangium lamarckii: "A small tree of the tropics of the Old World. On the coast of Malabar, the fruit is an article of food. It affords an edible fruit. The fruit in India is mucilaginous, sweet, somewhat astringent but is eaten."

Albizia julibrissin (Federbaum): "Asia and tropical Africa. The aromatic leaves are used by the Chinese as food. The leaves are said to be edible. The tree is called nemu in Japan."

Albizia lucida: "East Indies. The edible, oily seeds taste like a hazelnut."

Albizia montana: "Java. Sometimes used as a condiment in Java."

Albizia myriophylla: "East Indies. With bark of this tree, the mountaineers make an intoxicating liquor."

Albizia myriophylla: "East Indies. With bark of this tree, the mountaineers make an intoxicating liquor."

Albizia procera: "Tropical Asia and Australia. In times of scarcity, the bark is mixed with flour."

Albuca major: "South Africa. In Kaffraria, Thunberg says the succulent stalk, which is rather mucilaginous, is chewed by the Hottentots and other travellers by way of quenching thirst."

Aletris farinosa: "North America. This plant, says Masters, is one of the most intense bitters known, but, according to Rafinesque, the Indians eat its bulbs."

Aleurites trilobus (Lichtnußbaum): "Tropical Asia and Pacific Islands. This is a large tree cultivated in tropical countries for the sake of its nuts. It is native to the eastern islands of the Malayan Archipelago and of the Samoan gr'oup. In the Hawaiian Islands, it occurs in extensive forests. The kernels of the nut when dried and stuck on a reed are used by the Polynesians as a substitute for candles and as an article of food in New Georgia. When pressed they yield a large proportion of pure, palatable oil, also used as a drying oil for paint and known as walnut-oil and artist's-oil."

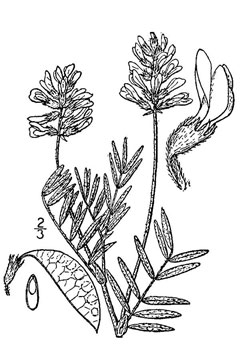

Alhagi maurorum: "North Africa to Hindustan. Near Kandahar and Herat, manna is found and collected on the bushes of this desert plant at flowering time after the spring rains. This manna is supposed by some to have been the manna of Scripture but others refer the manna of Scripture to one of the lichens."

Alisma plantago: "North temperate zone and Australia. The solid part of the root contains farinaceous matter and, when deprived of its acrid properties by drying, is eaten by the Calmucks."

Allium akaka: "Persia. This plant appears in the bazar in Teheren as a vegetable under the name of wolag. It also grows in the Alps. The whole of the young plant is considered a delicacy and is used as an addition to rice in a pilau."

Allium ampeloprasum (Perlzwiebel): "Europe and the Orient. This is a hardy perennial, remarkable for the size of the bulbs. The leaves and stems somewhat resemble those of the leek. The peasants in certain parts of Southern Europe eat it raw and this is its only known use."

Allium angulosum (Kantiger Lauch): "Siberia. Called on the upper Yenisei mischei-tschesnok, mouse garlic, and from early times collected and salted for winter use."

Allium ascalonicum (Wilder Lauch): "Cultivated everywhere. The Askolonion krommoon of Theophrastus and the Cepa ascolonia of Pliny, are supposed to be our shallot but this identity can scarcely be claimed as assured. It is not established that the shallot occurs in a wild state, and De Candolle is inclined to believe it is a form of A. cepa , the onion. It is mentioned and figured in nearly all the early botanies, and many repeat the statement of Pliny that it came from Ascalon, a town in Syria, whence the name. Michaud, in his History of the Crusades, says that our gardens owe to the holy wars shallots, which take their name from Ascalon. Amatus Lusitanus, 1554, gives Spanish, Italian, French and German names, which go to show its early culture in these countries. In England, shallots are said to have been cultivated in 1633, but McIntosh says they were introduced in 1548; they do not seem to have been known to Gerarde in 1597. In 1633, Worlidge says "eschalots art now from France become an English condiment." Shallots are enumerated for American gardens in 1806. Vilmorin mentions one variety with seven sub-varieties.

The bulbs are compound, separating into what are called cloves, like those of garlic, and are of milder flavor than other cultivated alliums. They are used in cookery as a seasoner in stews and soups, as also in a raw state; the cloves, cut into small sections, form an ingredient in French salads and are also sprinkled over steaks and chops. They make an excellent pickle. In China, the shallot is grown but is not valued as highly as is A. uliginosum."

Allium canadense (Kanada-Lauch): "North America. There is some hesitation in referring the tree onion of the garden to this wild onion. Loudon refers to it as "the tree, or bulb- bearing, onion, syn. Egyptian onion, A. cepa , var. viviparium; the stem produces bulbs instead of flowers and when these bulbs are planted they produce underground onions of considerable size and, being much stronger flavored than those of any other variety, they go farther in cookery." Booth says, "the bulb-bearing tree onion was introduced into England from Canada in 1820 and is considered to be a vivaparous variety of the common onion, which it resembles in appearance. It differs in its flower-stems being surmounted by a cluster of small green bulbs instead of bearing flowers and seed." It is a peculiarity of A. canadense that it often bears a head of bulbs in the place of flowers; its flavor is very strong; it is found throughout northern United States and Canada. Mueller says its top bulbs are much sought for pickles of superior flavor. Brown says its roots are eaten by some Indians. In 1674, when Marquette and his party journeyed from Green Bay to the present site of Chicago, these onions formed almost the entire source of food. The lumbermen of Maine often used the plant in their broths for flavoring. On the East Branch of the Penobscot, these onion occur in abundance and are bulb-producing on their stalks. They grow in the clefts of ledges and even with the scant soil attain a foot in height. In the lack of definite information, it may be allowable to suggest that the tree onion may be a hybrid variety from this wild species, or possibly the wild species improved by cultivation. The name, Egyptian onion, is against this surmise, while, on the other hand, its apparent origination in Canada is in its favor, as is also the appearance of the growing plants."

Allium cepa (Küchenzwiebel): "Persia and Beluchistan. The onion has been known and cultivated as an article of food from the earliest period of history. Its native country is unknown. At the present time it is no longer found growing wild, but all authors ascribe to it an eastern origin. Perhaps it is indigenous from Palestine to India, whence it has extended to China, Cochin China, Japan, Europe, North and South Africa and America. It is mentioned in the Bible as one of the things for which the Israelites longed in the wilderness and complained about to Moses. Herodotus says, in his time there was an inscription on the Great Pyramid stating the sum expended for onions, radishes and garlic, which had been consumed by the laborers during the progress of its erection, as 1600 talents. A variety was cultivated, so excellent that it received worship as a divinity, to the great amusement of the Romans, if Juvenal is to be trusted. Onions were prohibited to the Egyptian priests, who abstained from most kinds of pulse, but they were not excluded from the altars of the gods. Wilkinson says paintings frequently show a priest holding them in his hand, or covering an altar with a bundle of their leaves and roots. They were introduced at private as well as public festivals and brought to table. The onions of Egypt were mild and of an excellent flavor and were eaten raw as well as cooked by persons of all classes.

Hippocrates says that onions were commonly eaten 430 B. C. Theophrastus, 322 B. C., names a number of varieties, the Sardian, Cnidian, Samothracian and Setanison, all named from the places where grown. Dioscorides, 60 A. D., speaks of the onion as long or round, yellow or white. Columella, 42 A. D., speaks of the Marsicam, which the country people call unionem, and this word seems to be the origin of our word, onion, the French ognon. Pliny, 79 A. D., devotes considerable space to cepa, and says the round onion is the best, and that red onions are more highly flavored than the white. Palladius, 210 A. D., gives minute directions for culture. Apicius, 230 A. D., gives a number of recipes for the use of the onion in cookery but its uses by this epicurean writer are rather as a seasoner than as an edible. In the thirteenth century, Albertus Magnus describes the onion but does not include it in his list of garden plants where he speaks of the leek and garlic, by which we would infer, what indeed seems to have been the case with the ancients, that it was in less esteem than these, now minor, vegetables. In the sixteenth century, Amatus Lusitanus says the onion is one of the commonest of vegetables and occurs in red and white varieties, and of various qualities, some sweet, others strong, and yet others intermediate in savor. In 1570, Matthiolus refers to varieties as large and small, long, round and flat, red, bluish, green and white. Laurembergius, 1632, says onions differ in form, some being round, others, oblong; in color, some white, others dark red; in size, some large, others small; in their origin, as German, Danish, Spanish. He says the Roman colonies during the time of Agrippa grew in the gardens of the monasteries a Russian sort which attained sometimes the weight of eight pounds. He calls the Spanish onion oblong, white and large, excelling all other sorts in sweetness and size and says it is grown in large abundance in Holland. At Rome, the sort which brings the highest price in the markets is the Caieta; at Amsterdam, the St. Omer.

There is a tradition in the East, as Glasspoole writes, that when Satan stepped out of the Garden of Eden after the fall of man, onions sprang up from the spot where he placed his right foot and garlic from that where his left foot touched.

Targioni-Tozzetti thinks the onion will probably prove identical with A. fistulosum Linn., a species having a rather extended range in the mountains of South Russia and whose southwestern limits are as yet unascertained.

The onion has been an inmate of British gardens, says McIntosh, as long as they deserve the appellation. Chaucer," about 1340, mentions them: "Wel loved he garleek, onyons and ek leekes.

Humboldt says that the primitive Americans were acquainted with the onion and that it was called in Mexicanxonacatl. Cortez, in speaking of the edibles which they found on the march to Tenochtitlan, cites onions, leeks and garlic. De Candollel does not think that these names apply to the species cultivated in Europe. Sloane, in the seventeenth century, had seen the onion only in Jamaica in gardens. The word xonacati is not in Hernandez, and Acosta says expressly that the onions and garlics of Peru came originally from Europe. It is probable that onions were among the garden herbs sown by Columbus at Isabela Island in 1494, although they are not specifically mentioned. Peter Martyr speaks of "onyons" in Mexico and this must refer to a period before 1526, the year of his death, seven years after the discovery of Mexico. It is possible that onions, first introduced by the Spaniards to the West Indies, had already found admittance to Mexico, a rapidity of adaptation scarcely impossible to that civilized Aztec race, yet apparently improbable at first thought.

Onions are mentioned by Wm. Wood, 1629-33, as cultivated in Massachusetts; in 1648, they were cultivated in Virginia; and were grown at Mobile, Ala., in 1775. In 1779, onions were among the Indian crops destroyed by Gen. Sullivan near Geneva, N. Y. In 1806, McMahon mentions six varieties in his list of American esculents. In 1828, the potato onion, A. cepa , var. aggregatum G. Don, is mentioned by Thorburn as a "vegetable of late introduction into our country." Burr describes fourteen varieties.

Vilmorin describes sixty varieties, and there are a number of varieties grown in France which are not noted by him. In form, these may be described as flat, flattened, disc-form, spherical, spherical-flattened, pear-shaped, long. This last form seems to attain an exaggerated length in Japan, where they often equal a foot in length. In 1886, Kizo Tamari, a Japanese commissioner to this country, says, "Our onions do not have large, globular bulbs. They are grown just like celery and have long, white, slender stalks." In addition to the forms mentioned above, are the top onion and the potato onion. The onion is described in many colors, such as white, dull white, silvery white, pearly white, yellowish- green, coppery-yellow, salmon-yellow, greenish-yellow, bright yellow, pale salmon, salmon-pink, coppery-pink, chamois, red, bright red, blood-red, dark red, purplish."

Allium cernuum: "Western New York to Wisconsin and southward. This and A. canadense formed almost the entire source of food for Marquette and his party on their journey from Green Bay to the present site of Chicago in the fall of 1674."

Allium fistulosum: "Siberia, introduced into England in 1629. The Welsh onion acquired its name from the German walsch (foreign). It never forms a bulb like the common onion but has long, tapering roots and strong fibers. It is grown for its leaves which are used in salads. McIntosh says it has a small, flat, brownish-green bulb which ripens early and keeps well and is useful for pickling. It is very hardy and, as Targioni-Tozzetti thinks, is probably the parent species of the onion. It is mentioned by McMahon in 1806 as one of the American garden esculents; by Randolph in Virginia before 1818; and was cataloged for sale by Thorburn in 1828, as at the present time."

Allium neapolitanum (Neapellauch): "Europe and the Orient. According to Heldreich, it yields roots which are edible."

Allium obliquum: "Siberia. From early times the plant has been cultivated on the Tobol as a substitute for garlic."

Allium odorum (Chinesischer Schnittlauch): "Siberia. This onion is eaten as a vegetable in Japan."

Allium oleraceum (Gemüse-Lauch): "Europe. The young leaves are used in Sweden to flavor stews and soups or fried with other herbs and are sometimes so employed in Britain but are inferior to those of the cultivated garlic."

Allium porrum (Porree): "Found growing wild in Algiers but the Bon Jardinier says it is a native of Switzerland. It has been cultivated from the earliest times. This vegetable was the prason of the ancient Greeks, the porrum of the Romans, who distinguished two kinds, the capitatum, or leek, and the sectile, or chives, although Columella, Pliny, and Palladius, indicate these as forms of the same plant brought about through difference of culture, the chive-like form being produced by thick planting. In Europe, the leek was generally known throughout the Middle Ages, and in the earlier botanies some of the figures of the leek represent the two kinds of planting alluded to by the Roman writers. In England, 1726, Townsend says that "leeks are mightily used in the kitchen for broths and sauces." The Israelites complained to Moses of the deprivation from the leeks of Egypt during their wanderings in the wilderness. Pliny states, that in his time the best leeks were brought from Egypt, and names Aricia in Italy as celebrated for them. Leeks were brought into great notice by the fondness for them of the Emperor Nero who used to eat them for several days in every month to clear his voice, which practice led the people to nickname him Porrophagus. The date of its introduction into England is given as 1562, but it certainly was cultivated there earlier, for it has been considered from time immemorial as the badge of Welshmen, who won a victory in the sixth century over the Saxons which they attributed to the leeks they wore by the order of St. David to distinguish them in the battle. It is referred to by Tusser and Gerarde as if in common use in their day.

The leek may vary considerably by culture and often attain a large size; one with the blanched portion a foot long and nine inches in circumference and the leaf fifteen inches in breadth and three feet in length has been recorded. Vilmorin described eight varieties in 1883 but some of these are scarcely distinct. In 1806, McMahon named three varieties among American garden esculents. Leeks are mentioned by Romans as growing at Mobile, Ala., in 1775 and as cultivated by the Choctaw Indians. The reference to leeks by Cortez is noticed under A. cepa, the onion. The lower, or blanched, portion is the part generally eaten, and this is used in soups or boiled and served as asparagus. Buist names six varieties. The blanched stems are much used in French cookery."

Allium reticulatum: "North America. This is a wild onion whose root is eaten by the Indians."

Allium roseum (Rosenlauch): "Mediterranean countries. According to Heldreich, this plant yields edible roots."

Allium rotundum (Runder Lauch): "Europe and Asia Minor. The leaves are eaten by the Greeks of Crimea."

Allium rubellum: "Europe, Siberia and the Orient. The bulbs are eaten by the hill people of India and the leaves are dried and preserved as a condiment."

Allium sativum (Knoblauch): "Europe. This plant, well known to the ancients, appears to be native to the plains of western Tartary and at a very early period was transported thence over the whole of Asia (excepting Japan), north Africa and Europe. It is believed to be the skorodon hemeron of Dioscorides and the allium of Pliny. It was ranked by the Egyptians among gods in taking an oath, according to Pliny. The want of garlics was lamented to Moses by the Israelites in the wilderness. Homer makes garlic a part of the entertainment which Nestor served to his guest, Machaon. The Romans are said to have disliked it on account of the strong scent but fed it to their laborers to strengthen them and to their soldiers to excite courage. It was in use in England prior to 1548 and both Turner and Tusser notice it. Garlic is said to have been introduced in China 140-86 B. C. and to be found noticed in various Chinese treatises of the fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Loureiro found it under cultivation in Cochin China.

The first mention of garlic in America is by Peter Martyr, who states that Cortez fed on it in Mexico. In Peru, Acosta says "the Indians esteem garlike above all the roots of Europe." It was cultivated by the Choctaw Indians in gardens before 1775 and is mentioned among garden esculents by American writers on gardening in 1806 and since. The plant has the well-known alliaceous odor which is strongly penetrating, especially at midday. It is not as much used by northern people as by those of the south of Europe. In many parts of Europe, the peasantry eat their brown bread with slices of garlic which imparts a flavor agreeable to them. In seed catalogs, the sets are listed while seed is rarely offered. There are two varieties, the common and the pink."

Allium schoenoprasum (Schnittlauch): "North temperate zone. This perennial plant seems to be grown in but few American gardens, although McMahon, 1806, included it in his list of American esculents. Chive plants are included at present among the supplies offered in our best seed catalogs. In European gardens, they are cultivated for the leaves which are used in salads, soups and for flavoring. Chives are much used in Scotch families and are considered next to indispensable in omelettes and hence are much more used on the Continent of Europe, particularly in Catholic countries. In England, chives were described by Gerarde as "a pleasant Sawce and good Pot- herb;" by Worlidge in 1683; the chive was among seedsmen's supplies in 1726; and it is recorded as formerly in great request but now of little regard, by Bryant in 1783.

The only indication of variety is found in Noisette, who enumerates the civette, the cive d'Angleterre and the cive de Portugal but says these are the same, only modified by soil. The plant is an humble one and is propagated by the bulbs; for, although it produces flowers, these are invariably sterile according to Vilmorin."

Allium scorodoprasum (Schlangen-Lauch): "Europe, Caucasus region and Syria. This species grows wild in the Grecian Islands and probably elsewhere in the Mediterranean regions. Loudon says it is a native of Denmark, formerly cultivated in England for the same purposes as garlic but now comparatively neglected. It is not of ancient culture as it cannot be recognized in the plants of the ancient Greek and Roman authors and finds no mention of garden cultivation by the early botanists. It is the Scorodoprasum of Clusius, 1601, and the Allii genus, ophioscorodon dictum quibusdam , of J. Bauhin, 1651, but there is no indication of culture in either case. Ray, 1688, does not refer to its cultivation in England. In 1726, however, Townsend says it is "mightly in request;" in 1783, Bryant classes it with edibles. In France it was grown by Quintyne, 1690. It is mentioned by Gerarde as a cultivated plant in 1596. Its bulbs are smaller than those of garlic, milder in taste and are produced at the points of the stem as well as at its base. Rocambole is mentioned among American garden esculents by McMahon, 1806, by Gardiner and Hepburn, 1818, and by Bridgeman, 1832."

Allium senescens (Berg-Lauch): "Europe and Siberia. This species is eaten as a vegetable in Japan."

Allium sphaerocephalon (Kugelköpfiger Lauch): "Europe and Siberia. From early times this species has been eaten by the people about Lake Baikal."

Allium stellatum (Prärie-Lauch): "North America. Bulb oblong-ovate and eatable."

Allium ursinum (Bärlauch): "Europe and northern Asia. Gerarde, 1597, says the leaves were eaten in Holland. They were also valued formerly as a pot-herb in England, though very strong. The bulbs were also used boiled and in salads. In Kamchatka this plant is much prized. The Russians as well as the natives gather it for winter food."

Allium vineale (Weinberg-Lauch): "Europe and now naturalized in northern America near the coast. In England, the leaves are used as are those of garlic."

Allophylus cobbe: "Eastern Asia. The berries, which are red in color and about the size of peas, are eaten by the natives."

Allophylus zeylanicus: "Himalayas. The fruit is eaten."

Alocasia indica: "East Indies and south Asia, South Sea Islands and east Australia. The underground stems constitute a valuable and important vegetable of the native dietary in India. The stems sometimes grow to an immense size and can be preserved for a considerable time, hence they are of great importance in jail dietary when fresh vegetables become scarce in the bazar or jail-garden. For its esculent stems and small, pendulous tubers of its root, it is cultivated in Bengal and is eaten by people of all ranks in their curries. In the Polynesian islands its large tuberous roots are eaten. Wilkes says the natives of the Kingsmill group of islands cultivate this species with great care. The root is said to grow to a very large size."

Alocasia macrorhiza (Alokasie): "Tropics of Asia, Australia and the islands of the Pacific. The root is eaten in India, after being cooked, but it is inferior to that of A. esculentum The roots are also eaten in tropical America as well as by the people of New Caledonia, who cultivate it. It furnishes the roasting eddas of Jamaica and the tayoea of Brazil. It is the taro of New Holland, the roots of which, when roasted, afford a staple aliment to the natives. Wilkes states that this plant is the ape of the Tahitians and is cultivated as a vegetable."

Aloe sp.: "The Banians of the African coast, according to Grant, cut the leaves of an aloe into small pieces, soak them in lime-juice, put them in the sun, and a pickle is thus formed."

Alpinia galanga (Galgant): "Tropical eastern Asia. The root is used in place of ginger in Russia and in some other countries for flavoring a liquor called nastoika. By the Tartars, it is taken with tea." In Cochin China the fresh root is used to season fish and for other economic purposes."

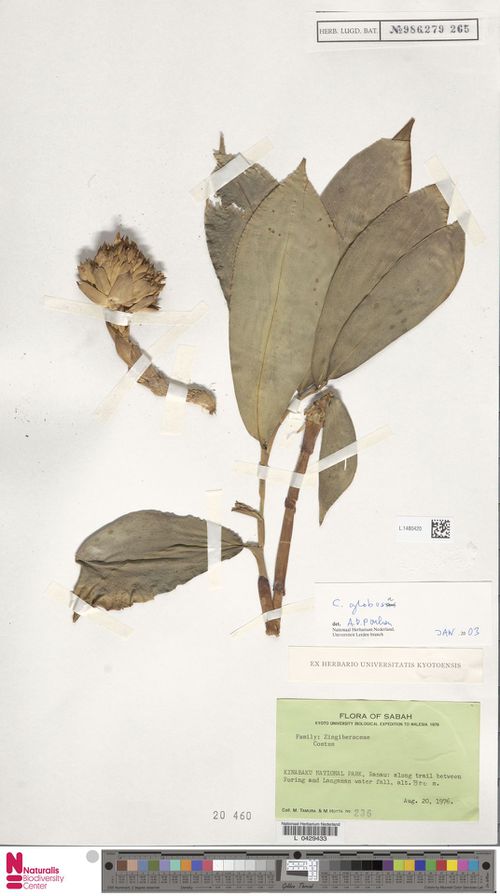

Alpinia globosa: "China. The large, round China cardamons are supposed to be produced by this species. The Mongol conquerors of China set great store on this fruit as a spice."

Alpinia striata (Javakardamom): "East Indies. This is probably the amomon of Dioscorides. It is found in Sumatra, Java and other East Indian islands as far as Burma and produces the round cardamoms of commerce."

Alpinia uviformis: "Tropical Asia. The fruit is said to be edible."

Alsodeia (Rinorea) physiphora: "Brazil. Used as a spinach in Brazil. The green leaves are very mucilaginous, and the negroes about Rio Janeiro eat them with their food."

Alsophila lunulata: "Viti. The young leaves are eaten in times of scarcity."

Alsophila spinulosa: "This is the pugjik of the Lepchas who eat the soft, watery pith. It is abundant in East Bengal and the peninsula of India."

Alstroemeria haemantha: "Chile. The plant furnishes a farina from its roots."

Alstroemeria ligtu: "Chile and the mountains of Peru. A farina is obtained from its roots. It is called in Peru Untu, in Chile utat. Its roots furnish a palatable starch."

Alstroemeria revoluta: "Chile. Its roots furnish a farina."

Alstroemeria versicolor: "Chile. A farina is obtained from its roots. In France it is an inmate of the flower garden."

Althaea officinalis (Eibisch): "The plant is found wild in Europe and Asia and is naturalized in places in America. It is cultivated extensively in Europe for medicinal purposes, acting as a demulcent. In 812, Charlemagne enjoined its culture in France. Johnson says its leaves may be eaten when boiled."

Althaea rosea (Stockrose): "The Orient. This species grows wild in China and in the south of Europe. Forskal says it is cultivated at Cairo for the sake of its leaves, which are esculent and are used in Egyptian cookery. It possesses similar properties to the marshmallow and is used for similar purposes in Greece."

Amaranthus blitum (Aufsteigender Amarant): "Temperate and tropical zones. The plant finds use as a pot-herb."

Amaranthus campestris (Weisser Amarant): "East Indies. This species is one of the pot-herbs of the Hindus."

Amaranthus diacanthus (Dorniger Amarant): "North America. Rafinesque says the leaves are good to eat as spinach."

Amaranthus gangeticus (Dreifarben-Amarant): "Tropical zone. This amaranthus is cultivated by the natives in endless varieties and is in general use in Bengal. The plant is pulled up by the root and carried to market in that state. The leaves are used as a spinach. Roxburgh says there are four leading varieties cultivated as pot-herbs: Viridis, the common green sort, is most cultivated; Ruber, a beautiful, bright colored variety; Albus, much cultivated in Bengal; Giganteus, is five to eight feet high with a stem as thick as a man's wrist. The soft, succulent stem is sliced and eaten as a salad, or the tops are served as an asparagus. In China, the plant is eaten as a cheap, cooling, spring vegetable by all classes. It is much esteemed as a pot- herb by all ranks of natives. This species is cultivated about Macao and the neighboring part of China and is the most esteemed of all their summer vegetables."

Amaranthus paniculatus (Ausgebreiteter Fuchsschwanz): "North America and naturalized in the Orient. This plant is extensively cultivated in India for its seed which is ground into flour. It is very productive. Roxburgh says it will bear half a pound of floury, nutritious seed on a square yard of ground. Titford says it forms an excellent potherb in Jamaica when boiled, exactly resembling spinach."

Amaranthus polygamus: "Tropical Africa and East Indies. This plant is cultivated in India and is used as a pot-herb. It has mucilaginous leaves without taste. This amaranthus is a common weed everywhere in India and is much used by the natives as a pot-herb. Drury says it is considered very wholesome. This species is the goose-foot of Jamaica, where it is sometimes gathered and used as a green."

Amaranthus polystachyus: "East Indies. The species is cultivated in India as a pot-herb for its mucilaginous leaves but is tasteless."

Amaranthus retroflexus (Ackerfuchsschwanz): "North America. This weed occurs around dwellings in manured soil in the United States whence it was introduced from tropical America. It is an interesting fact that it is cultivated by the Arizona Indians for its seeds."

Amaranthus spinosus (Dorniger Amarant): "Tropical regions. This is a weed in cultivated land in Asia, Africa and America. It is cultivated sometimes as a spinach. In Jamaica, it is frequently used as a vegetable and is wholesome and agreeable. It seems to be the prickly calalue of Long."

Amaranthus viridis (Grüner Fuchsschwanz): "Tropics. This plant is stated by Titford to be an excellent pot-herb in Jamaica and is said to resemble spinach when boiled."

Ambelania acida: "Guiana. The fruit is edible."

Amelanchier alnifolia (Erlenblättrige Felsenbirne): "North America. In Oregon and Washington, the berries are largely employed as a food by the Indians. The fruit is much larger than that of the eastern service berry; growing in favorable localities, each berry is full half an inch in diameter and very good to eat."

Amelanchier canadensis (Kanadische Felsenbirne): "North America and eastern Asia. This bush or small tree, according to the variety, is a native of the northern portion of America and eastern Asia. Gray describes five forms. For many years a Mr. Smith, Cambridge, Massachusetts, has cultivated var. oblongifolia in his garden and in 1881 exhibited a plate of very palatable fruit at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society's show. The berries are eaten in large quantities, fresh or dried, by the Indians of the Northwest. The fruit is called by the French in Canadapoires, in Maine sweet pear and from early times has been dried and eaten by the natives. It is called grape-pear in places, and its fruit is of a purplish color and an agreeable, sweet taste. The pea-sized fruit is said to be the finest fruit of the Saskatchewan country and to be used by the Cree Indians both fresh and dried."

Amelanchier vulgaris: "Mountains of Europe and adjoining portions of Asia. This species has long been cultivated in England, where its fruit, though not highly palatable, is eatable. It is valued more for its flowers than its fruit."

Ammobroma sonorae: "A leafless plant, native of New Mexico (Nope - MM) . Col. Grey, the original discoverer of this plant, found it in the country of the Papago Indians, a barren, sandy waste, where rain scarcely ever falls, but "where nature has provided for the sustenance of man one of the most nutritious and palatable of vegetables." The plant is roasted upon hot coals and ground with mesquit beans and resembles in taste the sweet potato "but is far more delicate." It is very abundant in the hills; the whole plant, except the top, is buried in the sand."

Amomum angustifolium (Ingwer): "Madagascar. This plant grows on marshy grounds in Madagascar and affords in its seeds the Madagascar, or great cardamoms of commerce. It is called there longouze."

Amomum aromaticum: "East Indies. The fruit is used as a spice and medicine by the natives and is sold as cardamoms."

Amomum granum-paradisi: "African tropics. The seeds are made use of illegally in England to give a fictitious strength to spirits and beer, but they are not particularly injurious. The seeds resemble and equal camphor in warmth and pungency."

Amomum maximum: "Java and other Malay islands. This species is said to be cultivated in the mountains of Nepal."

Amomum melegueta: "African tropics. The seeds are exported from Guiana where the plant, supposed to have been brought from Africa, is cultivated by the negroes. The hot and peppery seeds form a valued spice in many parts of India and Africa."

Amomum villosum: "East Indies and China. This plant is supposed to yield the hairy, round, China cardamoms."

Amomum xanthioides: "Burma. In China, says Smith, the seeds are used as a preserve or condiment and are used in flavoring spirit."

Amorphophallus campanulatus (Elefantenkartoffel): "Tropical Asia. This plant is much cultivated, especially in the northern Circars, where it is highly esteemed for the wholesomeness and nourishing quality of its roots. The telinga potato is cooked in the manner of the yam and is also used for pickling. When in flower, the odor exhaled is most overpowering, resembling that of carrion, and flies cover the club of the spadix with their eggs. The root is very acrid in a raw state; it is eaten either roasted or boiled. At the Society Islands the fruit is eaten as bread, when breadfruit is scarce and in the Fiji Islands is highly esteemed for its nutritive properties."

Amorphophallus lyratus: "East Indies. The roots are eaten by the natives and are thought to be very nutritious. They require, however, to be carefully boiled several times and to be dressed in a particular manner in order to divest them of a somewhat disagreeable taste."

Amphicarpaea edgeworthii: "Himalayas. A wild, bean-like plant, the pods of which are gathered while green and used for food."

Amphicarpaea monoica: "North America. A delicate vine growing in rich woodlands which bears two kinds of flowers, the lower ones subterranean and producing fruit. It is a native of eastern United States. Porcher says that in the South the subterranean pod is cultivated as a vegetable and is called hog peanut."

Amphicarpaea monoica: "North America. A delicate vine growing in rich woodlands which bears two kinds of flowers, the lower ones subterranean and producing fruit. It is a native of eastern United States. Porcher says that in the South the subterranean pod is cultivated as a vegetable and is called hog peanut."

Anacardium humile: "Brazil. The nuts are eaten and conserves are made of the fruit."

Anacardium nanum: "Brazil. The nuts are eaten and conserves are made of the fruit."

Anacardium occidentale (Cashew): "This tree is indigenous to the West Indies, Central America, Guiana, Peru and Brazil in all of which countries it is cultivated. The Portuguese transplanted it as early as the sixteenth century to the East Indies and Indian archipelago. Its existence on the eastern coast of Africa is of still more recent date, while neither China, Japan, or the islands of the Pacific Ocean possess it. The shell of the fruit has thin layers, the intermediate one possessing an acrid, caustic oil, called cardol, which is destroyed by heat, hence the kernels are roasted before being eaten; the younger state of the kernel, however, is pronounced wholesome and delicious when fresh. Drury says the kernels are edible and wholesome, abounding in sweet, milky juice and are used for imparting a flavor to Madeira wine. Ground and mixed with cocoa, they make a good chocolate. The juice of the fruit is expressed, and, when fermented, yields a pleasant wine; distilled, a spirit is drawn from the wine making a good punch. A variety of the tree is grown in Travancore, probably elsewhere, the pericarp of the nuts of which has no oil but may be chewed raw with impunity. An edible oil equal to olive oil or almond oil is procured from the nuts but it is seldom prepared, the kernels being used as a table fruit. A gum, similar to gum arable, calledcadju gum, is secreted from this tree. The thickened receptacle of the nut has an agreeable, acid flavor and is edible."

Anacardium rhinocarpus: "South America. This is a noble tree of Columbia and British Guiana, where it is called wild cashew. It has pleasant, edible fruits like the cashew. In Panama, according to Seemann, the tree is called espave, in New Granada caracoli."

Anagallis arvensis (Acker-Gauchheil): "Europe and temperate Asia. Pimpernel, according to Fraas, is eaten as greens in the Levant. Johnson says it forms a part of salads in France and Germany. The flowers close at the approach of bad weather, hence the name, poor man's weatherglass."

Ananas sativus (Ananas): "Tropical America. In 1493, the companions of Columbus, at Guadeloupe island, first saw the pineapple, the flavor and fragrance of which astonished and delighted them, as Peter Martyr records. The first accurate illustration and description appear to have been given by Oviedo in 1535. Las Casas, who reached the New World in 1502, mentions the finding by Columbus at Porto Bello of the delicious pineapple. Oviedo, who went to America in 1513, mentions in his book three kinds as being then known. Benzoni, whose History of the New World was published in 1568 and who resided in Mexico from 1541 to 1555, says that no fruit on God's earth could be more agreeable, and Andre Thevet, a monk, says that in his time, 1555-6, the nanas was often preserved in sugar. De Soto, 1557, speaks of "great pineapples of a very good smell and exceeding good taste" in the Antilles. Jean de Lery, 1578, describes it in his Voyage to Brazil as being of such excellence that the gods might luxuriate upon it and that it should only be gathered by the hand of a Venus. Acosta, 1578, also describes this fruit as of " an excellent smell, and is very pleasant and delightful in taste, it is full of juice, and of a sweet and sharp taste." He calls the plant ananas. Raleigh, 1595, speaks of the " great abundance of pinas, the princesse of fruits, that grow under the Sun, especially those of Guiana.

Acosta states that the ananas was carried from Santa Cruz in Brazil to the West Indies, and thence to the East Indies and China, but he does not pretend by this that pineapples were not to be found out of Brazil, for he describes an idol in Mexico, Vitzili-putzli, as having "in his left hand a white target with the figures of five pineapples, made of white feathers, set in a crosse." Stephens, at Tuloom, on the coast of Yucatan, found what seemed intended to represent a pineapple among the stucco ornaments of a ruin. We do not know what to make of Wilkinson's n statement of one instance of the pineapple in glazed pottery being among the remains from ancient Egypt. It has probably been cultivated in tropical America from time immemorial, as it now rarely bears seeds. Humboldt mentions pineapples often containing seeds as growing wild in the forests of the Orinoco, at Esmeralda; and Schomburgk found the wild fruit, bearing seeds, in considerable quantity throughout Guiana. Piso also mentions a pineapple having many seeds growing wild in Brazil. Titford says this delicious fruit is well known and very common in Jamaica, where there are several sorts. Unger says, in 1592 it was carried to Bengal and probably from Peru by way of the Pacific Ocean to China. Ainslie says that it was introduced in the reign of the Emperor Akbar by the Portuguese who brought the seed from Malacca; that it was naturalized in Java as early as 1599 and was taken thence to Europe. In 1594, it was cultivated in China, brought thither perhaps from America by way of the Philippines. An anonymous writer states that it was quite common in India in 1549 and this is in accord with Acosta's statement.

The pineapple is now grown in abundance about Calcutta, and Firminger describes ten varieties. It is now a common plant in Celebes and the Philippine Islands. The Jesuit, Boymins, mentions it in his Flora Sinensis of 1636. A white kind in the East Indies, says Unger, which has run wild, still contains seed in its fruit. In 1777, Captain Cook planted pineapples in various of the Pacific Isles, as at Tongatabu, Friendly Islands, and Society Islands. Afzelius says pineapples grow wild in Sierra Leone and are cultivated by the natives. Don states that they are so abundant in the woods as to obstruct passage and that they bear fruit abundantly. In Angola, wild pines are mentioned by Montiero, and the pineapple is noticed in East Africa by Krapf. R. Brown speaks of the pineapples as existing upon the west coast of Africa but he admits its American origin. In Italy, the first attempts at growing pineapples were made in 1616 but failed. At Leyden, a Dutch gardener was successful in growing them in 1686. The fruit, as imported, was known in England in the time of Cromwell and is again noticed in 1661 and in 1688 from Barbados. The first plants introduced into England came from Holland in 1690, but the first success at culture dates from 1712."

Anaphalis margaritacea (Großblütiges Perlkörbchen): "North America. Josselyn, prior to 1670, remarks of this plant that "the fishermen when they want tobacco, take this herb: being cut and dryed." In France, it is an inmate of the flower garden."

Anchomanes hookeri: "Eastern equatorial Africa. The large bulb is boiled and eaten."

Anchusa officinalis (Ochsenzunge): "Europe. Johnson says, in the south of France and in some parts of Germany, where it is common, the young leaves are eaten as a green vegetable."

Ancistrophyllum secundiflorum (Rattan-Palme): "African tropics. The stems are cut into short lengths and are carried by the natives upon long journeys, the soft central parts being eaten after they have been properly roasted."

Andropogon schoenanthus: "Asia, African tropics and subtropics. This species is commonly cultivated for the fine fragrance of the leaves which are often used for flavoring custard. When fresh and young, the leaves are used in many parts of the country as a substitute for tea and the white center of the succulent leaf-culms is used to impart a flavor to curries. The tea made of this grass is considered a wholesome and refreshing beverage, says Wallich, and her Royal Majesty was supplied with the plant from the Royal Gardens, Kew, England."

Angelica atropurpurea: "North America. This plant is found from New England to Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and northward. Stillel says the stems are sometimes candied. The root is used in domestic medicines as an aromatic and stimulant."

Angelica officinalis (archangelica) (Engelwurz): "Europe, Siberia and Himalayan regions. This plant is a native of the north of Europe and is found in the high, mountainous regions in south Europe, as in Switzerland and among the Pyrenees. It is also found in Alaska. Angelica is cultivated in various parts of Europe and is occasionally grown in American gardens. The whole plant has a fragrant odor and aromatic properties. Angelica is held in great estimation in Lapland, where the natives strip the stem of leaves, and the soft, internal part, after the outer skin has been pulled off, is eaten raw like an apple or turnip. In Kamchatka, the roots are distilled and a kind of spirit is made from them, and on the islands of Alaska, where it is abundant and called wild parsnip, it is stated by Dall to be edible. Angelica has been in cultivation in England since 1568. The leaf-stalks were formerly blanched and eaten like celery. The plant is in request for the use of confectioners, who make an excellent sweetmeat with the tender stems, stalks, and ribs of the leaves candied with sugar. The seeds enter into the composition of many liquors. In the north of Europe, the leaves and stalks are still used as a vegetable.

The medicinal properties of the root were highly prized in the Middle Ages. In Pomet, we read that the seed is much used to make angelica comfits as well as the root for medicine. Bryant deems it the best aromatic that Europe produces. This plant must be a native of northern Europe, for there are no references to it in the ancient authors of Greece and Rome, nor is it mentioned by Albertus Magnus in the thirteenth century. By Fuchsius, 1542, and succeeding authors it receives proper attention. The German name, Heilige Geist Wurz, implies the estimation in which it was held and offers a clue to the origin of the word Angelica, or angel plant, which occurs in so many languages, as in English, Spanish, Portugese, and Italian, becoming Angelique and Archangelique in French, and Angelickwurz in German. Other names of like import are the modern Engelwurz in Germany, Engelkruid in Flanders and Engelwortel in Holland.

The various figures given by herbalists show the same type of plant, the principal differences to be noted being in the size of the root. Pena and Lobel, 1570, note a smaller variety as cultivated in England, Belgium, and France, and Gesner is quoted by Camerarius as having seen roots of three pounds weight. Bauhin, 1623, says the roots vary, the Swissgrown being thick, those of Bohemia smaller and blacker.

Garden angelica is noticed amongst American garden medicinal herbs by McMahon, 1806, and the seed is still sold by our seedsmen."

Angelica sylvestris (Wald-Engelwurz): "Europe and the adjoining portions of Asia. On the lower Volga, the young stems are eaten raw by the natives. Don says it is used as archangelica, but the flavor is more bitter and less grateful."

Angiopteris erecta (Madagaskar Baum-Farn): "A fern of India, the Asiastic and Polynesian Islands. The caudex, as also the thick part of the stipes, is of a mealy and mucilaginous nature and is eaten by the natives in times of scarcity."

Angraecum fragrans: "The leaves of this orchid are very fragrant and are used in Bourbon as tea. It has been introduced into France."

Anisophyllea laurina: "African tropics. The fruit is sold in the markets of Sierra Leone in the months of April and May; it is described by Don as being superior to any other which is tasted in Africa. It is of the size and shape of a pigeon's egg, red on the sunned side, yellow on the other, its flavor being something between that of the nectarine and a plum."

Annesorhiza capensis: "Cape of Good Hope. The root is eaten."

Annesorhiza montana: "South Africa. The plant has an edible root."

Annona asiatica: "Ceylon and cultivated in Cochin China. The oblong-conical fruit, red on the outside, is filled with a whitish, .eatable pulp but is inferior in flavor to that of A. squamosa."

Annona cherimola: "American tropics. Originally from Peru, this species seems to be naturalized only in the mountains of Port Royal in Jamaica. Venezuela, New Granada and Brazil know it only as a plant of cultivation. It has been carried to the Cape Verde Islands and to Guinea. The cherimoya is not mentioned among the fruits of Florida by Atwood in 1867 but is included in the American Pomological Society's list for 1879. In 1870, specimens were growing at the United States Conservatory in Washington. The fruit is esteemed by the Peruvians as not inferior to any fruit of the world. Humboldt speaks of it in terms of praise. Herndon says Huanuco is par excellence the country of the celebrated cherimoya, and that he has seen it there quite twice as large as it is generally seen in Lima and of the most delicious flavor. Masters says, however, that Europeans do not confirm the claims of the cherimoya to superiority among fruits, and the verdict is probably justified by the scant mention by travellers and the limited diffusion."

Annona cinerea (Rahmapfel): "West Indies. This species is placed by Unger among edible fruit-bearing plants."

Annona muricata (Sauersack): "Tropical America. This tree grows wild in Barbados and Jamaica but in Surinam has only escaped from gardens. It is cultivated in the whole of Brazil, Peru and Mexico. In Jamaica, the fruit is sought after only by negroes. The plant has quite recently been carried to Sierra Leone. It is not mentioned among the fruits of Florida by Atwood in 1867 but is included in the American Pomological Society's list for 1879. The smell and taste of the fruit, flowers and whole plant resemble much those of the black currant. The pulp of the fruit, says Lunan, is soft, white and of a sweetish taste, intermixed with oblong, dark colored seeds, and, according to Sloane, the unripe fruit dressed like turnips tastes like them. Morelet says the rind of the fruit is thin, covering a white, unctuous pulp of a peculiar, but delicious, taste, which leaves on the palate a flavor of perfumed cream. It has a peculiarly agreeable flavor although coupled with a biting wild taste. Church says its leaves form corossol tea."

Annona paludosa: "Guiana, growing upon marshy meadows. The species bears elongated, yellow berries, the size of a hen's egg, which have a juicy flesh."

Annona palustris (Alligatorapfel): "American and African tropics. The plant bears fruit the size of the fist. The seeds, as large as a bean, lie in an orange-colored pulp of an unsavory taste but which has something of the smell and relish of an orange. The fruit is considered narcotic and even poisonous in Jamaica but of the latter we have, says Lunan, no certain proof. The wood of the tree is so soft and compressible that the people of Jamaica call it corkwood and employ it for stoppers."

Annona punctata: "Guiana. The plant bears a brown, oval, smooth fruit about three inches in diameter with little reticulations on its surface. The flesh is reddish, gritty and filled with little seeds. It has a good flavor and is eaten with pleasure. It is the pinaou of Guiana."

Annona reticulata (Netzannone): "Tropical America. Cultivated in Peru, Brazil, in Malabar and the East Indies. This delicious fruit is produced in Florida in excellent perfection as far north as St. Augustine ; it is easily propagated from seed. Masters says its yellowish pulp is not so much relished as that of the soursop or cherimoyer. Lunan says, in Jamaica, the fruit is much esteemed by some people. Unger says it is highly prized but he calls the fruit brown, the size of the fist, while Lunan says brown, shining, of a yellow or orange color, with a reddishness on one side when ripe."

Annona senegalensis: "African tropics and Guiana. The fruit is not much larger than a pigeon's egg but its flavor is said, by Savine, to be superior to most of the other fruits of this genus."

Annona squamosa (Rahmapfel): "It is uncertain whether the native land of this tree is to be looked for in Mexico, or on the plains along the mouth of the Amazon. Von Martius found it forming forest groves in Para. It is cultivated in tropical America and the West Indies and was early transported to China, Cochin China, the Philippines and India. The fruit is conical or pear- shaped with a greenish, imbricated, scaly shell. The flesh is white, full of long, brown granules, very aromatic and of an agreeable strawberry- like, piquant taste. Rhind says the pulp is delicious, having the odor of rose water and tasting like clotted cream mixed with sugar. Masters says the fruit is highly relished by the Creoles but is little esteemed by Europeans. Lunan says it is much esteemed by those who are fond of fruit in which sweet prevails. Drury says the fruit is delicious to the taste and on occasions of famine in India has literally proved the staff of life to the natives."

Anthemis nobilis (Echte Römische Kamille): "Europe. Naturalized in Delaware. This plant is largely cultivated for medicinal purposes in France, Germany and Italy. It has long been cultivated in kitchen gardens, an infusion of its flowers serving as a domestic remedy. The flowers are occasionally used in the manufacture of bitter beer and, with wormwood, make to a certain extent a substitute for hops. It has been an inmate of American gardens from an early period. In France it is grown in flower-gardens."

Anthericum hispidum: "South Africa. The sprouts are eaten as a substitute for asparagus. They are by no means unpalatable, says Carmichael,9 though a certain clamminess which they possess, that induces the sensation as of pulling hairs from between one's lips, renders them at first unpleasant."

Anthistiria imberbis (Känguru-Gras): "Africa. This grass grows in great luxuriance in the Upper Nile region, 5° 5' south, and in famines furnishes the natives with a grain."

Anthriscus cerefolium (Kerbel): "Europe, Orient and north Asia. This is an old fashioned pot-herb, an annual, which appears in garden catalogs. Chervil is said to be a native of Europe and was cultivated in England by Gerarde in 1597. Parkinson says "it is sown in gardens to serve as salad herb." Pliny mentions its use by the Syrians, who cultivated it as a food, and ate it both boiled and raw. Booth says the French and Dutch have scarcely a soup or a salad in which chervil does not form a part and as a seasoner is by many preferred to parsley. It seems still to find occasional use in England, Chervil was cultivated in Brazil in 1647 but there are no references to its early use in America. The earlier writers on American gardening mention it, however, from McMahon in 1806. The leaves, when young, are the parts used to impart a warm, aromatic flavor to soups, stews and salads. Gerarde speaks of the roots as being edible. There are curled-leaved varieties."

Antidesma bunius (Salamanderbaum): "A tree of Nepal, Amboina and Malabar. Its shining, deep red, fruits are subacid and palatable. In Java, the fruits are used, principally by Europeans, for preserving."

Antidesma diandrum: "East Indies. The berries are eaten by the natives. The leaves are acid and are made into preserve."

Antidesma ghesaembilla: "East Indies, Malay, Australia and African tropics. The small drupes, dark purple when ripe, with pulp agreeably acid, are eaten."

Apios tuberosa (Amerikanische Erdbirne): "Northeast America. The tubers are used as food. Kalm says this is the kopniss of the Indians on the Delaware, who ate the roots; that the Swedes ate them for want of bread, and that in 1749 some of the English ate them instead of potatoes. Winslow says that the Pilgrims, during their first winter, "were enforced to live on ground nuts." At Port Royal, in 1613, Biencourt and his followers used to scatter about the woods and shores digging ground nuts. In France, the plant is grown in the flower garden."

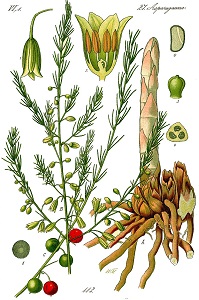

Apium graveolens (Sellerie): "A plant of marshy places whose habitat extends from Sweden southward to Algeria, Egypt, Abyssinia and in Asia even to the Caucasus, Baluchistan and the mountains of British India and has been found in Tierra del Fuego, in California and in New Zealand. Celery is supposed to be the selinon of the Odyssey, the selinon heleion of Hippocrates, the eleioselinon of Theophrastus and Dioscorides and the helioselinon of Pliny and Palladius. It does not seem to have been cultivated, although by some commentators the plant known as smallage has a wild and a cultivated sort. Nor is there one clear statement that this smallage was used as food, for sativus means simply planted as distinguished from growing wild, and we may suppose that this Apium, if smallage was meant, was planted for medicinal use. Targioni-Tozzetti says this Apium was considered by the ancients rather as a funereal or ill-omened plant than as an article of food, and that by early modern writers it is mentioned only as a medicinal plant. This seems true, for Fuchsius, 1542, does not speak of its being cultivated and implies a medicinal use alone, as did Walafridus Strabo in the ninth century; Tragus, 1552; Pinaeus, 1561; Pena and Lobel, 1570, and Ruellius' Dioscorides , 1529. Camerarius' Epitome of Matthiolus , 1586, says planted also in gardens; and Dodonaeus, in his Pemptades, 1616, speaks of the wild plant being transferred to gardens but distinctly says not for food use. According to Targioni-Tozzetti, Alamanni, in the sixteenth century, speaks of it, but at the same time praises Alexanders for its sweet roots as an article of food. Bauhin's names, 1623, Apium palustre and Apium officinarum , indicate medicinal rather than food use, and J. Bauhin's name, Apium vulgare ingratus , does not promise much satisfaction in the eating. According to Bretschneider, celery, probably smallage, can be identified in the Chinese work of Kia Sz'mu, the fifth century A. D., and is described as a cultivated plant in the Nung Cheng Ts'nan Shu, 1640. We have mention of a cultivated variety in France by Olivier de Serres, 1623, and in England the seed was sold in 1726 for planting for the use of the plant in soups and broths; and Miller says, 1722, that smallage is one of the herbs eaten to purify the blood. Cultivated smallage is now grown in France under the name Celeri a couper , differing but little from the wild form. The number of names that are given to smallage indicate antiquity.