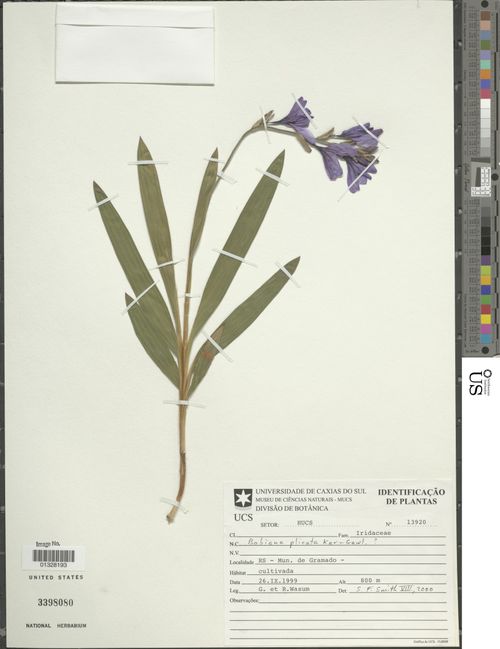

Babiana plicata: "South Africa. The root is sometimes boiled and eaten by the colonists at the Cape."

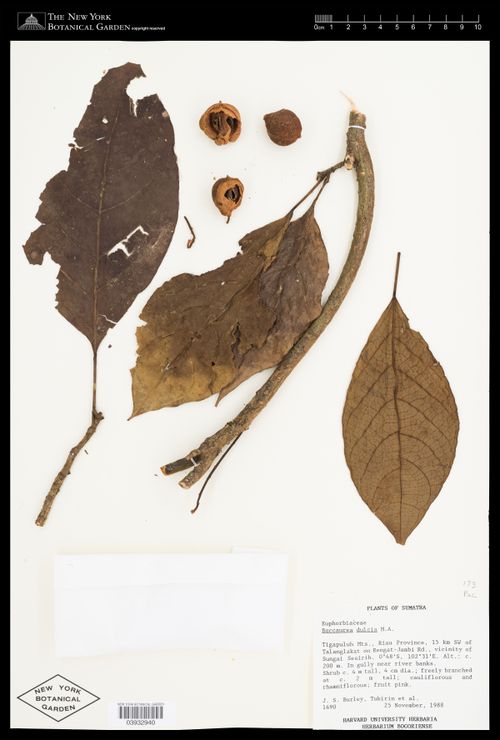

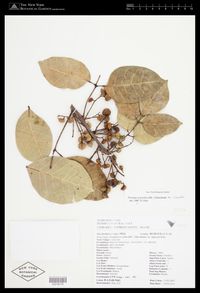

Baccaurea dulcis: "South Africa. The root is sometimes boiled and eaten by the colonists at Malayan Archipelago; cultivated in China. The fruits of this species are rather larger than a cherry, nearly round and of a yellowish color. The pulp is luscious and sweet and is greatly eaten in Sumatra, where the tree is called choopah and in Malacca, where it goes by the name of rambeh."

Baccaurea sapida: "East Indies and Malay. This plant is cultivated for its agreeable fruits. The Hindus call it lutqua.

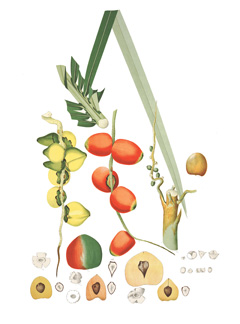

Bactris gasipaes: "Venezuela. On the Amazon, says Bates, this plant does not grow wild but has been cultivated from time immemorial by the Indians. The fruit is dry and mealy and may be compared in taste to a mixture of chestnuts and cheese. Bunches of sterile or seedless fruit sometimes occur at Ega and at Para. It is one of the principal articles of food at Ega when in season and is boiled and eaten with treacle and salt. Spencer compares the taste of the mealy pericarp, when cooked, to a mixture of potato and chestnut but says it is superior to either. Seemann says in most instances the seed is abortive, the whole fruit being a farinaceous mass. Humboldt says every cluster contains from 50 to 80 fruits, yellow like apples but purpling as they ripen, two or three inches in diameter, and generally without a kernel; the farinaceous portion is as yellow as the yolk of an egg, slightly saccharine and exceedingly nutritious. He found it cultivated in abundance along the upper Orinoco. In Trinidad, the peach palm is said to be very prolific, bearing two crops a year, at one season the fruit all seedless and another season bearing seeds. The seedless fruits are highly appreciated by natives of all classes."

Bactris major: "West Indies. The fruit is the size of an egg with a succulent, purple coat from which wine may be made. The nut is large, with an oblong kernel and is sold in the markets under the name of cocorotes."

Bactris maraja: "Brazil. This palm has a fruit of a pleasant, acid flavor from which a vinous beverage is prepared."

Bactris minor: "Jamaica. The fruit is dark purple, the size of a cherry and contains an acid juice which Jacquin says is made into a sort of wine. The fruit is edible but not pleasant."

Bagassa guianensis: "Guiana. The tree bears an orange-shaped edible fruit."

Balanites aegyptica: "Northern Africa, Arabia and Palestine. A shrubby, thorny bush of the southern border of the Sahara from the Atlantic to Hindustan. It is called in equatorial Africa m'choonchoo; the edible drupe tastes like an intensely bitter date."

Balsamorhiza hookeri: "Northwestern America. The thick roots of this species are eaten raw by the Nez Perce Indians and have, when cooked, a sweet and rather agreeable taste."

Balsamorhiza sagittata: "Northwestern America. The roots are eaten by the Nez Perce Indians in Oregon, after being cooked on hot stones. They have a sweet and rather agreeable taste. Wilkes mentions the Orgeon sunflower of which the seeds, pounded into a meal called mielito, are eaten by the Indians of Puget Sound."

Bambusa arundinacea: "East Indies. The seeds of this and other species of Bambusa have often saved the lives of thousands in times of scarcity in India, as in Orissa in 1812, in Kanara in 1864 and in 1866 in Malda. The plant bears whitish seed, like rice, and Drury says these seeds are eaten by the poorer classes."

Bambusa tulda: "East Indies and Burma. In Bengal, the tender young shoots are eaten as pickles by the natives."

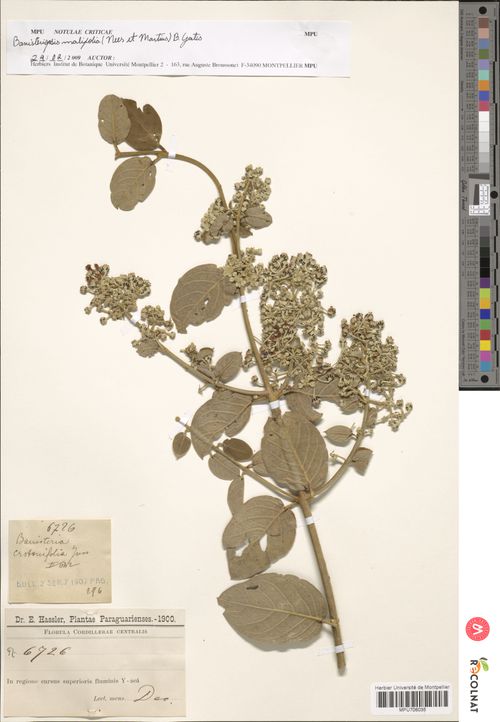

Banisteria crotonifolia: "Brazil. The fruit is eaten in Brazil."

Baptisia tinctoria (Wilder Indigo): "Northeastern America. Barton says the young shoots of this plant, which resemble asparagus in appearance, have been used in New England as a substitute for asparagus."

Barbarea arcuata (Krummfrüchtige Winterkresse): "Europe and Asia. The plant serves as a bitter cress."

Barbarea praecox: "Europe. This cress is occasionally cultivated for salad in the Middle States under the name scurvy grass and is becoming spontaneous farther south. It is grown in gardens in England as a cress and is used in winter and spring salads. In Germany, it is generally liked. In the Mauritius, it is regular cultivation and is known as early winter cress. In the United States, its seeds are offered in seed catalogs."

Barbarea vulgaris (Barbarakraut): "Europe and temperate Asia. This herb of northern climates has been cultivated in gardens in England for a long time as an early salad and also in Scotland, where the bitter leaves are eaten by some. In early times, rocket was held in some repute but is now banished from cultivation yet appears in gardens as a weed. The whole herb, says Don, has a nauseous, bitter taste and is in some degree mucilaginous. In Sweden, the leaves are boiled as a kale. In New Zealand, the plant is used by the natives as a food under the name, toi. Rocket is included in the list of American garden esculents by McMahon, in 1806. In 1832, Bridgeman says winter cress is used as a salad in spring and autumn and by some boiled as a spinage."

Barringtonia butonica: "Islands of the Pacific. This plant has oleaginous seeds and fruits which are eaten green as vegetables."

Barringtonia careya: "Australia. The fruit is large, with an adherent calyx and is edible."

Barringtonia edulis: "Fiji Islands. The rather insipid fruit is eaten either raw or cooked by the natives."

Barringtonia excelsa: "India, Cochin China and the Moluccas. The fruit is edible and the young leaves are eaten cooked and in salad."

Basella rubra: "Tropical regions. This twining, herbaceous plant is cultivated in all parts of India, and the succulent stems and leaves are used by the natives as a pot-herb in the way of spinach. In Burma, the species is cultivated and in the Philippines is seemingly wild and eaten by the natives. It is also cultivated in the Mauritius and in every part of India, where it occurs wild. Malabar nightshade was introduced to Europe in 1688 and was grown in England in 1691, but these references can hardly apply to the vegetable garden. It is, however, recorded in French gardens in 1824 and 1829. It is grown in France as a vegetable, a superior variety having been introduced from China in 1839. According to Livingstone, it is cultivated as a pot-herb in India. It is a spinach plant which has somewhat the odor of Ocimum basilicum. The species is cultivated in almost every part of India as a spinach, and an infusion of the leaves in used as tea. It is called Malabar nightshade by Europeans of India."

Bassia butyracea: "East Indies. The pulp of the fruit is eatable. The juice is extracted from the flowers and made into sugar by the natives. It is sold in the Calcutta bazaar and has all the appearance of date sugar, to which it is equal if not superior in quality. An oil is extracted from the seeds, and the oil cake is eaten as also is the pure vegetable butter which is called chooris and is sold at a cheap rate."

Bassia latifolia: "East Indies. The succulent flowers fall by night in large quantities from the tree, are gathered early in the morning, dried in the sun and sold in the bazaars as an important article of food. They have a sickish, sweet taste and smell and are eaten raw or cooked. The ripe and unripe fruit is also eaten, and from the fruit is expressed an edible oil."

Bassia longifolia: "East Indies. The flowers are eaten by the natives of Mysore, either dried, roasted, or boiled to a jelly. The oil pressed from the fruits is to the common people of India a substitute for ghee and cocoanut oil in their curries."

Batis maritima: "Jamaica. This low, erect, succulent plant is used as a pickle."

Bauhinia esculenta: "South Africa. The root is sweet and nutritious."

Bauhinia lingua: "Moluccas. This species is used as a vegetable."

Bauhinia purpurea: "East Indies, Burma and China. The flower-buds are pickled and eaten as a vegetable."

Bauhinia tomentosa: "Asia and tropical Africa. The seeds are eaten in the Punjab, and the leaves are eaten by natives of the Philippines as a substitute for vinegar."

Bauhinia vahlii: "East Indies. The pods are roasted and the seeds are eaten. Its seeds taste, when ripe, like the cashew-nut."

Bauhinia variegata: "East Indies, Burma and China. There are two varieties, one with purplish, the other with whitish flowers. The leaves and flower-buds are eaten as a vegetable and the flower-buds are often pickled in India."

Beckmannia erucaeformis: "Europe, temperate Asia and North America. According to Engelmann, the seeds are collected for food by the Utah Indians."

Begonia barbata: "East Indies and Burma. The leaves, called tengoor, are eaten by the natives as a pot-herb. Hooker says the stems of many species are eaten in the Himalayas, when cooked, being pleasantly acid. The stems are made into a sauce in Sikkim."

Begonia cucullata: "Brazil. The leaves are used as cooling salads."

Begonia malabarica: "East Indies. Henfrey says the plants are eaten as pot-herbs."

Begonia picta: "Himalayas. The leaves have an acid taste and are used as food."

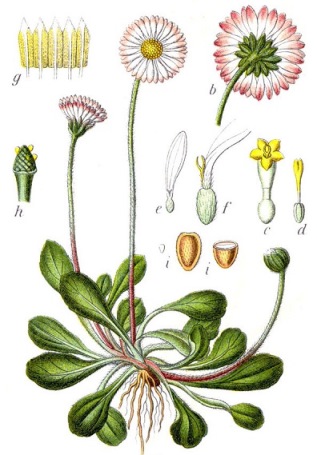

Bellis perennis (Gänseblümchen): "Europe and the adjoining portions of Asia. Lightfoot says the taste of the leaves is somewhat acid, and, in scarcity of garden-stuff, they have been used in some countries as a pot-herb."

Bellucia aubletii: "Guiana. A tree of Guiana which has an edible, yellow fruit."

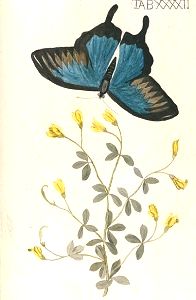

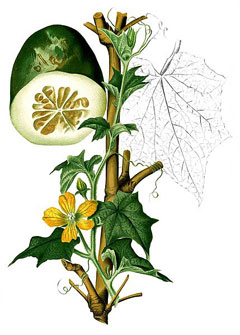

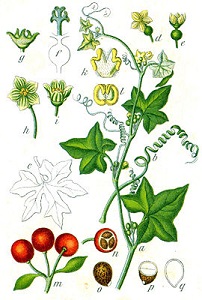

Benincasa cerifera: "Asia and African tropics. This annual plant is cultivated in India for its very large, handsome, egg-shaped gourd. The gourd is covered with a pale greenish-white, waxen bloom. It is consumed by the natives in an unripe state in their curries. This gourd is cultivated throughout Asia and its islands and in France as a vegetable. It is described as delicate, quite like the cucumber and preferred by many. The bloom of the fruit forms peetha wax and occurs in sufficient quantity to be collected and made into candles. This cucurbit has been lately introduced into European gardens. According to Bret-schneider, it can be identified in a Chinese book of the fifth century and is mentioned as cultivated in Chinese writings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In 1503- 08, Ludovico di Varthema describes this gourd in India under the name como-langa. In 1859, Naudin says it is much esteemed in southern Asia, particularly in China, and that the size of its fruit, its excellent keeping qualities, the excellence of its flesh and the ease of its culture should long since have brought it into garden culture. He had seen two varieties: one, the cylindrical, ten to sixteen inches long and one specimen twenty-four inches long by eight to ten inches in diameter, from Algiers; the other, an ovoid fruit, shorter, yet large, from China. The long variety was grown at the New York Agricultural Experiment Station in 1884 from seed from France. The fruit is oblong-cylindrical, resembling very closely a watermelon when, unripe but when ripe covered with a heavy glaucous bloom.

This plant is recorded in herbariums as from the Philippine Islands, New Guinea, New Caledonia, Fiji Islands, Tahiti, New Holland and southern China and as cultivated in Japan and in China."

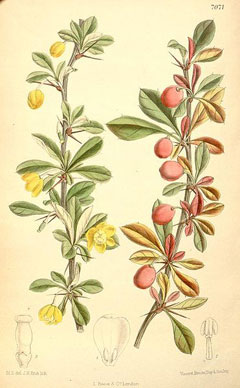

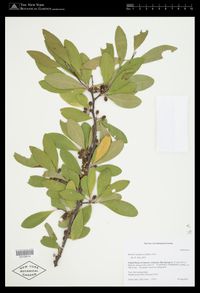

Berberis angulosa: "India. This is a rare Himalayan species with the largest flowers and fruit of any of the thirteen species found on that range. In Sikkim, it is a shrub four or more feet in height, growing at an elevation of from 11,000 to 13,000 feet, where it forms a striking object in autumn from the rich golden and red coloring of its foliage. The fruit is edible and less acid than that of the common species."

Berberis aquifolium: "Western North America. This shrub is not rare in cultivation as an ornamental. It has deep blue berries in clusters somewhat resembling the frost grape and the flavor is strongly acid. The berries are used as food, and the juice when fermented makes, on the addition of sugar, a palatable and wholesome wine. It is said not to have much value as a fruit. It is common in Utah and its fruit is eaten, being highly prized for its medicinal properties. The acid berry is made into confections and eaten as an antiscorbutic, under the name mountain grape."

Berberis aristata: "East Indies. The Nepal barberry produces purple fruits covered with a fine bloom, which in India are dried in the sun like raisins and used like them at the dessert. It is native to the mountains of Hindustan and is called in Arabic aarghees. The plants are quite hardy and fruit abundantly in English gardens. Downing cultivated it in America but it gave him no fruit. In Nepal, the berries are dried by the Hill People and are sent down as raisins to the plains."

Berberis asiatica: "Region of Himalayas. According to Lindley, the fruit is round, covered with a thick bloom and has the appearance of the finest raisins. The berries are eaten in India. The plants are quite hardy and fruit abundantly in English gardens."

Berberis buxifolia: "Region of Himalayas. According to Lindley, the fruit is round, coveredThis evergreen shrub is found native from Chile to the Strait of Magellan. According to Dr. Philippi, it is the best of the South American species; the berries are quite large, black, hardly acid and but slightly astringent. The fruit, says Sweet, is used in England both green and ripe as are gooseberries, for making pies and tarts. In Valdivia and Chiloe, provinces of Chile, they are frequently consumed. It has ripened fruit at Edinburgh, and Mr. Cunningham enthusiastically says it is as large as the Hamburg grape and equally good to eat. It is also grown in the gardens of the Horticultural Society, London, from which cions appear to have been distributed. Under the name Black Sweet Magellan, it is noticed as a variety in Downing. It was introduced into England about 1828."

Berberis canadensis: "North America; a species found in the Alleghenies of Virginia and southward but not in Canada. The berries are red and of an agreeable acidity."

Berberis darwinii: "Chile and Patagonia. In Devonshire, England, the cottagers preserve the berries when ripe, and a party of school children admitted to where there are plants in fruit will clear the bushes of every berry as eagerly as if they were black currants."

Berberis empetrifolia: "Region of Magellan Strait. The berry is edible."

Berberis glauca: "New Granada. The berry is edible."

Berberis lycium: "Himalayan region. In China, the fruit is preserved as in Europe, and the young shoots and leaves are made use of as a vegetable or for infusion as a tea."

Berberis nepalensis: "An evergreen of the Himalayas. The fruits are dried as raisins in the sun and sent down to the plains of India for sale."

Berberis nervosa: "Northwestern America; pine forests of Oregon. The fruit resembles in size and taste that of B. aquifolium."

Berberis pinnata: "Mexico; a beautiful, blue-berried barberry very common in New Mexico. It is called by the Mexicans lena amorilla. The berries are very pleasant to the taste, being saccharine with a slight acidity."

Berberis sibirica: "Siberia. The berry is edible."

Berberis sinensis: "China. The berry is edible."

Berberis tomentosa: "Chile. The berry is edible."

Berberis tomentosa: "Chile. The berry is edible."

Berberis trifoliolata: "Western Texas. The bright red, acid berries are used for tarts and are less acid than those of B. vulgaris."

Berberis vulgaris: "Europe and temperate Asia. This barberry is sometimes planted in gardens in England for its fruit. It was early introduced into the gardens of New England and increased so rapidly that in 1754 the Province of Massachusetts passed an act to prevent its spreading. The berries are preserved in sugar, in syrup, or candied and are esteemed by some. They are also occasionally pickled in vinegar, or used for flavoring. There are varieties with yellow, white, purple, and black fruits. A celebrated preserve is made from a stoneless variety at Rouen, France. The leaves were formerly used to season meat in England. The berries are imported from Afghanistan into India under the name of currant. A black variety was found by Tournefort on the bank of the Euphrates, the fruit of which is said to be of delicious flavor."

Bertholletia excelsa: "Brazil. This is one of the most majestic trees of Guiana, Venezuela and Brazil. It furnishes the triangular nuts of commerce everywhere used as a food. It was first described in 1808. An oil is expressed from the kernels and the bark is used in caulking ships."

Besleria violacea: "Guiana. The purple berry is edible."

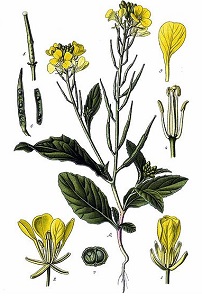

Beta vulgaris (Zuckerrübe): "Europe and north Africa. The beet of the garden is essentially a modem vegetable. It is not noted by either Aristotle or Theophrastus, and, although the root of the chard is referred to by Dioscorides and Galen, yet the context indicates medicinal use. Neither Columella, Pliny nor Palladius mentions its culture, but Apicius, in the third century, gives recipes for cooking the root of Beta, and Athenaeus, in the second or third century, quotes Diphilus of Siphnos as saying that the beet-root was grateful to the taste and a better food than the cabbage. It is not mentioned by Albertus Magnus in the thirteenth century, but the word bete occurs in English recipes for cooking in 1390.

Barbarus, who died in 1493, speaks of the beet as having a single, long, straight, fleshy, sweet root, grateful when eaten, and Ruellius, in France, appropriates the same description in 1536, as does also Fuchsius in 1542; the latter figures the root as described by Barbarus, having several branches and small fibres. In 1558, Matthiolus says the white and black chards are common in Italian gardens but that in Germany they have a red beet with a swollen, turnip-like root which is eaten. In 1570, Pena and Lobel speak of the same plant but apparently as then rare, and, in 1576, Lobel figures this beet, and this figure shows the first indication of an improved form, the root portion being swollen in excess over the portion by the collar. This beet may be considered the prototype of the long, red varieties. In 1586, Camerarius figures a shorter and thicker form, the prototype of our half-long blood beets. This same type is figured by Daleschamp, 1587, and also a new type, the Beta Romana, which is said in Lyte's Dodoens, 1586, to be a recent acquisition. It may be considered as the prototype of our turnip or globular beets.

Another form is the flat-bottomed red, of which the Egyptian and the Bassano of Vilmorin, as figured, may be taken as the type. The Bassano was to be found in all the markets of Italy in 1841, and the Egyptian was a new sort about Boston in 1869. Nothing is known concerning the history of this type.

The first appearance of the improved beet is recorded in Germany about 1558 and in England about 1576, but the name used, Roman beet, implies introduction from Italy, where the half-long type was known in 1584. We may believe Ruellius's reference in 1536 to be for France. In 1631, this beet was in French gardens under the name, Beta rubra pastinaca, and the culture of "betteraves" was described in Le Jardinier Solitaire, 1612. Gerarde mentions the "Romaine beete" but gives no figure. In 1665, in England, only the Red Roman was listed by Lovell, and the Red beet was the only kind noticed by Townsend, a seedsman, in 1726, and a second sort, the common Long Red, is mentioned in addition by Mawe, 1778, and by Bryant, 1783. In the United States, one kind only was in McMahon's catalog of 1806 — the Red beet, but in 1828 four kinds are offered for sale by Thorbum. At present, Vilmorin describes seventeen varieties and names and partly describes many others.

Chard was the beta of the ancients and of the Middle Ages. Red chard was noticed by Aristotle about 350 B. C. Theophrastus knew two kinds—the white, called Sicula, and the black (or dark green), the most esteemed. Dioscorides also records two kinds. Eudemus, quoted by Athenaeus, in the second century, names four; the sessile, the white, the common and the dark, or swarthy. Among the Romans, chard finds frequent mention, as by Columella, Pliny, Palladius and Apicius. In China is was noticed in writings of the seventh, eighth, fourteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; in Europe, by all the ancient herbalists. Chard has no Sanscrit name. The ancient Greeks called the species teutlion; the Romans, beta; the Arabs, seig; the Nabateans, silq. Albertus Magnus, in the thirteenth century, uses the word acelga, the present name in Portugal and Spain. The wild form is found in the Canary Isles, the whole of the Mediterranean region as far as the Caspian, Persia and Babylon, perhaps even in western India, as also about the sea-coasts of Britain. It has been sparingly introduced, into kitchen-gardens for use as a chard. The red, white, and yellow forms are named from quite early times; the red by Aristotle, the white and dark green by Theophrastus and Disocorides. In 1596, Bauhin describes dark, red, white, yellow, chards with a broad stalk and the sea-beet. These forms, while the types can be recognized, yet have changed their appearance in our cultivated plants, a greater compactness and development being noted as arising from the selection and cultivation which has been so generally accorded in recent times. Among the varieties Vilmorin describes are the White, Swiss, Silver, Curled Swiss, and Chilian.

The sugar beet is a selected form from the common beet and scarcely deserves a separate classification. Varieties figured by Vilmorin are all of the type of the half-long red, and agree in being mostly underground and in being very or quite scaly about the collar. The sugar beet has been developed through selection 6f the roots of high sugar content for the seedbearers. The sugar beet industry was born in France in 1811, and in 1826 the product of the crop was 1,500 tons of sugar. The use of the sugar beet could not, then, have preceded 1811; yet in 1824 five varieties, the grosse rouge, petite rouge, rouge ronde, jaune and blanche are noted and the French Sugar, or Amber, reached American gardens before 1828. A richness of from 16 to 18 per cent of sugar is now claimed for Vilmorin's new Improved White Sugar.

The discovery of sugar in the beet is credited to Margraff in 1747, having been announced in a memoir read before the Berlin Academy of Sciences."

Beta vulgaris (Sea Beet): "The leaves of the sea beet form an excellent chard and in Ireland are collected from the wild plant and used for food; in England the plant is sometimes cultivated in gardens. This form has been ennobled by careful culture, continued until a mangold was obtained."

Beta vulgaris (Mangold): "Mangolt was the old German name for chard, or rather for the beet species, but in recent times the mangold is a large-growing root of the beet kind used for forage purposes. In the selections, size and the perfection of the root above ground have been important elements, as well as the desire for novelty, and hence we have a large number of very distinct-appearing sorts: the long red, about two-thirds above ground; the olive-shaped, or oval; the globe; and the flat-bottomed Yellow d'Obendorf. The colors to be noted are red, yellow and white. The size often obtained in single specimens is enormous, a weight of 135 pounds has been, claimed in California, and Gasparin in France vouches for a root weighing 132 pounds.

Very little can be ascertained concerning the history of mangolds. They certainly are of modem introduction. Olivier de Serres, in France, 1629, describes a red beet which was cultivated for cattle-feeding and speaks of it as a recent acquisition from Italy. In England, it is said to have arrived from Metz in 1786; but there is a book advertised of which the following is the title: Culture and Use of the Mangel Wurzel, a Root of Scarcity, translated from the French of the Abbe de Commerell, by J. C. Lettson, with colored plates, third edition, 1787, by which it would appear that it was known earlier. McMahon records the mangold as in American culture in 1806. Vilmorin describes sixteen kinds and mentions many others."

Betula alba (Hänge-Birke): "Europe, northern Asia and North America. The bark, reduced to powder, is eaten by the inhabitants of Kamchatka, beaten up with the ova of the sturgeon, and the inner bark is ground into a meal and eaten in Lapland in times of dearth. Church says sawdust of birchwood is boiled, baked and then mixed with flour to form bread in Sweden and Norway. In Alaska, says Dall, the soft, new wood is cut fine and mingled with tobacco by the economical Indian. From the sap, a wine is made in Derbyshire, England, and, in 1814, the Russian soldiers near Hamburg intoxicated themselves with this fermented sap. The leaves are used in northern Europe as a substitute for tea, and the Indians of Maine make from the leaves of the American variety a tea which is relished. At certain seasons, the sap contains sugar. In Maine, the sap is sometimes collected in the spring and made into vinegar."

Betula lenta: "North America. The sap, in Maine, is occasionally converted into vinegar."

Betula nigra: "From Massachusetts to Virginia. The sap contains sugar in the spring, according to Henfrey."

Billardiera mutabilis: "Australia. This species is said by Backhouse to have pleasant, subacid fruit."

Bixa orellana: "South America. This shrub furnishes in the reddish pulp surrounding the seeds the annatto of commerce, imported from South America and used extensively for coloring cheese and butter. The culture of this plant is chiefly carried on in Guadeloupe and Cayenne, where the product is known as roucou. It is grown also in the Deccan and other parts of India and the Eastern Archipelago, in the Pacific Islands, Brazil, Peru, and Zanzibar, as Simmonds writes."

Blepharis edulis: "Persia, Northwestern India, Nubia and tropical Arabia. The leaves are eaten crude."

Blighia sapida: "Guinea. This small tree is a native of Guinea and was carried to Jamaica by Captain Bligh in 1793. It is much esteemed in the West Indies as a fruit. The fruit is fleshy, of a red color tinged with yellow, about three inches long by two in width and of a three-sided form. When ripe, it splits down the middle of each side, disclosing three shining, jet-black seeds, seated upon and partly immersed in a white, spongy substance called the aril. This aril is the eatable part. Fruits ripened in the hothouses of England have not been pronounced very desirable. Unger says, however, the seeds have a fine flavor when cooked and roasted with the fleshy aril."

Boerhaavia repens: "Cosmopolitan tropics. According to Ainslie, the leaves are eaten in India, and Graham says in the Deccan it is sometimes eaten by the natives as greens. It is a common and troublesome weed of India. The young leaves are eaten by the natives as greens and made into curries."

Bomarea edulis: "Tropical America. The roots are round and succulent and when boiled are said to be a light and delicate food. A farinaceous or mealy substance is also made of them, from which cream is made, wholesome and very agreeable to the taste. The roots are sold under the name of white Jerusalem artichoke."

Bomarea glaucescens: "Ecuador. The fruit is sought after by children on account of a sweet, gelatinous pulp, resembling that of the pomegranate, in which the seeds are imbedded."

Bomarea salsilla: "Chile. The tubers are available for human food."

Bombax ceiba: "South America. The leaves and buds, when young and tender, are very mucilaginous, like okra, and are boiled as greens by the negroes of Jamaica. The fleshy petals of the flowers are sometimes prepared as food by the Chinese. The tree is called god-tree in the West Indies, where it is native."

Bombax septenatum: "Tropical America. The plant furnishes a green vegetable."

Bongardia rauwolfii: "Greece and the Orient. This plant was noticed as early as 1573 by Rauwolf, who spoke of it as the true chrysogomum of Dioscorides. The Persians roast or boil the tubers and use them as food, while the leaves are eaten as are those of sorrel."

Boottia (Ottelia) cordata: "A water plant of Burma. All the green parts are eaten by the Burmese as pot-herbs, for which purpose they are collected in great quantity and carried to the market at Ava."

Boquila trifoliata: "Chile. The berries, about the size of a pea, are eaten in Chile. It is commonly called in Chile, baquil-blianca."

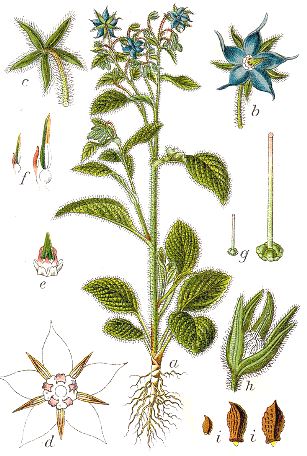

Borago officinalis (Boretsch): "Europe, North Africa and Asia Minor. This plant has been distributed throughout the whole of southern and middle Europe even in the humblest gardens and is now cultivated likewise in India, North America and Chile. Its leaves and flowers were used by the ancient Greeks and Romans for cool tankards. The Greeks called it euphrosynon, for, when put in a cup of wine, it made those who drank it merry. It has been used in England since the days of Parkinson. In Queen Elizabeth's time, both the leaves and flowers were eaten in salads. It is at present cultivated for use in cooling drinks and is used by some as a- substitute for spinach. The leaves contain so much nitre that when dry they bum like match paper. The leaves also serve as a garnish and are likewise pickled. In India, it is cultivated by Europeans for use in country beer to give it a pleasant flavor. Borage is enumerated by Peter Martyr as among the plants cultivated at Isabela Island by the companions of Columbus. It appears in the catalogs of our American seedsmen and is mentioned by almost all of the earlier writers of gardening. The flowering parts of borage are noted or figured by nearly all of the ancient herbalists."

Borassus flabellifer: "A common tree in a large part of Africa south of the Sahara and of tropical eastern Asia. The fruits, but still more the young seedlings, which are raised on a large scale for that purpose, are important as an article of food. Livingstone says the fibrous pulp around the large nuts is of a sweet, fruity taste and is eaten. The natives bury the nuts until the kernels begin to sprout; when dug up and broken, the inside resembles coarse potatoes and is prized in times of scarcity as nutritious food. During several months of the year, palm wine, or sura, is obtained in large quantities and when fresh is a pleasant drink, somewhat like champagne, and not at all intoxicating, though, after standing a few hours, it becomes highly so. Grant says on the Upper Nile the doub palm is called by the negroes m'voomo, and the boiled roots are eaten in famines by the Wanyamwezi.

The Palmyra palm is cultivated in India. The pulp of the fruit is eaten raw or roasted, and a preserve is made of it in Ceylon. The unripe seeds and particularly the young plant two or three months old are an important article of food. But the most valuable product of the tree is the sweet sap which runs from the peduncles, cut before flowering, and is collected in bamboo tubes or in earthern pots tied to the cut peduncle. Nearly all of the sugar made in Burma and a large proportion of that made in south India is the produce of this palm. The sap is also fermented into toddy and distilled. Drury says the fruit and fusiform roots are used as food by the poorer classes in the Northern Circars. Firminger says the insipid, gelatinous, pellucid pulp of the fruit is eaten by the natives but is not relished by Europeans. A good preserve may, however, be made from it and is often used for pickling."

Borbonia (Aspalathus) cordata: "South Africa. At the Cape of Good Hope, in 1772, Thunberg found the country people making tea of the leaves."

Boscia senegalensis: "African tropics. The seeds are eaten by the negroes of the Senegal."

Boswellia frereana: "Tropics of Africa. Though growing wild, the trees are carefully watched and even sometimes propagated. The resin is used in the East for chewing as is that of the mastic tree."

Boswellia serrata: "India. In times of famine, the Khnoods and Woodias live on a soup made from the fruit of this tree."

Botrychium virginianum: "This large, succulent fern is boiled and eaten in the Himalayas as well as in New Zealand."

Bouea burmanica: "Burma. The fruit is eaten, that of one variety being intensely sour, of another insipidly sweet."

Bourreria succulenta: "West Indies. The berries are the size of a pea, shining, saffron or orangecolored, pulpy, sweet, succulent and eatable."

Brabejum stellatifolium: "South Africa. Thunberg says the Hottentots eat the fruit of this shrub and that it is sometimes used by the country people instead of coffee, the outside rind being taken off and the fruit steeped in water to deprive it of its bitterness; it is then boiled, roasted and ground like coffee."

Brachistus solanaceus: "Nicaragua. This perennial merits trial culture on account of its large, edible tubers."

Brachystegia appendiculata: "Tropical Africa. The seeds are eaten."

Brahea dulcis: "Peru. This Mexican palm, called palma dulce and soyale, has a fruit which is a succulent drupe of a yellow color and cherry-size, sweet and edible."

Brahea (Serenoa) serrulata: "Southern United States. A fecula was formerly prepared from the pith by the Florida Indians."

Brasenia schreberi: "India, Japan, Australia, Tropical Africa and North America. The tuberous root-stocks are collected by the California Indians for food."

Brassica alba: "Europe and the adjoining portions of Asia. The cultivated plant appears to have been brought from central Asia to China, where the herbage is pickled in winter or used in spring as a pot-herb. In 1542, Fuchsius, a German writer, says it is planted everywhere in gardens. In 1597, in England, Gerarde says it is not common but that he has distributed the seed so that he thinks it is reasonably well known. It is mentioned in American gardens in 1806. The young leaves, cut close to the ground before the formation of the second series or rough leaves appear, form an esteemed salad."

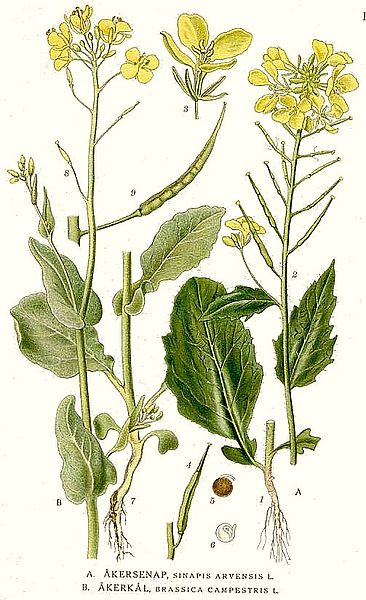

Brassica rapa campestris: "The turnip, says Unger, is derived from a species growing wild at the present day in Russia and Siberia as well as on the Scandinavian peninsula. From this, in course of cultivation, a race has been produced as B. campestris Linn., and a second as B. rapa Linn., our white turnip, with many varieties. The cultivation of this plant, indigenous in the region between the Baltic Sea and the Caucasus, was probably first attempted by the Celts and Germans when they were driven to make use of nutritious roots. Buckman was inclined to the belief that B. campestris and B. napus are but agrarian forms derived from B. oleracea. Nowhere, he asserted, are the first two varieties truly wild but both track cultivation throughout Europe, Asia and America. Lindley says this plant, B. campestris, has been found apparently wild in Lapland, Spain, the Crimea and Great Britain but it is difficult to say whether or not it is truly wild. When little changed by cultivation, it is the colsa, colza, or colsat, the chou oleifere of the French, an oil-reed plant of great value. This is the colsa of Belgium, the east of France, Germany and Switzerland but not of other districts, in which the name is applied to rape. Unger states that this plant, growing wild from the Baltic Sea to the Caucasus, is the B. campestris oleifera DC. or B. colza Lam. and that its culture, first starting in Belgium, is now extensively carried on in Holstein. De Candolle supposes the Swedish turnip is a variety, analogous to the kohl-rabi among cabbages, but with the root swollen instead of the stem. In its original wild condition, it is a flatfish, globular root, with a very fine tail, a narrow neck and a hard, deep yellow flesh. Buckman, by seeding rape and common turnips in mixed rows, secured, through hybridization, a small percentage of malformed swedes, which were greatly improved by careful cultivation. If Bentham was correct in classing B. napus with B. campestris, the result of Buckman's experiment does not carry the rutabaga outside of B. campestris for its origin. Don classifies the rutabaga as B. campestris Linn. var. oleifera, sub. var. rutabaga.

The turnip is of ancient culture. Columella, A. D. 42, says the napus and the rapa are both grown for the use of man and beast, especially in France; the former does not have a swollen but a slender root, and the latter is the larger and greener. He also speaks of the Mursian gongylis, which may be the round turnip, as being especially fine. The distinction between the napus and the rapa was not always held, as Pliny uses the word napus generically and says that there are five kinds, the Corinthian, Cleonaeum, Liothasium, Boeoticum and the Green. The Corinthian, the largest, with an almost bare root, grows on the surface and not, as do the rest, under the soil. The Liothasium, also called Thracium, is the hardest. The Boeoticum is sweet, of a notable roundness and not very long as is the Cleonaeum. At Rome, the Amitemian is in most esteem, next the Nursian, and third our own kind (the green?). In another place, under rapa, he mentions the broadbottom (flat?), the globular, and as the most esteemed, those of Nursia. The napus of Amiternum, of a nature quite similar to the rapa, succeeds best in a cool place. He mentions that the rapa sometimes attains a weight of forty pounds. This weight has, however, been exceeded in, modem times. Matthiolus, 1558, had heard of turnips that weighed a hundred pounds and speaks of having seen long and purple sorts that weighed thirty pounds. Amatus Lusitanus, 1524, speaks of turnips, weighing fifty and sixty pounds. In England, in 1792, Martyn says the greatest weight that he is acquainted with is thirty-six pounds. In California, about 1830, a turnip is recorded of one hundred pounds weight.

In the fifteenth century, Booth says the turnip had become known to the Flemings and formed one of their principal crops. The first turnips that were introduced into England, he says, are believed to have come from Holland in 1550. In the time of Henry VIII (1509-1547) according to Mclntosh, turnips were used baked or roasted in the ashes and the young shoots were used as a salad and as a spinach. Gerarde describes them in a number of varieties, but the first notice of their field culture is by Weston in 1645. Worlidge, 1668, mentions the turnip fly as an enemy of turnips and Houghton speaks of turnips as food for sheep in 1684. In 1686, Ray says they are sown everywhere in fields and gardens. In 1681, Worlidge says they are chiefly grown in gardens but are also grown to some extent in fields. The turnip was brought to America at a very early period. In 1540, Cartier sowed turnip seed in Canada, during his third voyage. They were also cultivated in Virginia in 1609; are mentioned again in 1648; and by Jefferson in 1781. They are said by Francis Higginson n to be in cultivation in Massachusetts in 1629 and are again mentioned by William Wood, 1629-33. They were plentiful about Philadelphia in 1707. Jared Sparks planted them in Connecticut in 1747. In 1775, Romans in his Natural History of Florida mentions them. They are also mentioned in South Carolina in 1779. In 1779, General Sullivan destroyed the turnips in the Indian fields at the present Geneva, New York, in the course of his invasion of the Indian country. The common flat turnip was raised as a field crop in Massachusetts and New York as early as 1817.

This turnip differs from the Brassica rapa oblonga DC. by its smooth and glaucous leaves. It surpasses other turnips by the sweetness of its flavor and furnishes white, yellow and black varieties. It is known as the Navet, or French turnip. This was apparently the napa of Columella.1 This turnip was certainly known to the early botanists, yet its synonymy is difficult to be traced from the figures."

Brassica carinata: "This plant is said by Unger to be found wild and cultivated in Abyssinia although it furnishes a very poor cabbage, not to be compared with ours."

Brassica chinensis: "The pe-tsai of the Chinese is an annual, apparently intermediate between cabbage and the turnip but with much thinner leaves than the former. It is of much more rapid growth than any of the varieties of the European cabbage, so much so, that when sown at midsummer it will ripen seed the same season. Introduced from China in 1837, it has been cultivated and used as greens by a few persons about Paris but it does not appear likely to become a general favorite. It is allied to the kales. Its seeds are ground into a mustard.

But little appears to be recorded concerning the varieties of this cabbage of which the Pak-choi and the Pe-tsai only have reached European culture. It has, however, been long under cultivation in China, as it can be identified in Chinese works on agriculture of the fifth, sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Loureiro, 1790, says it is also cultivated in Cochin China and varieties are named with white and yellow flowers. The Pak-choi has more resemblance to a chard than to a cabbage, having oblong or oval, dark shining-green leaves upon long, very white and swollen stalks. The Pe-tsai, however, rather resembles a cos lettuce, forming an elongated head, rather full and compact and the leaves are a little wrinkled and undulate at the borders. Both varieties have, however, a common aspect and are annuals.

Considering that the round-headed cabbage is the only sort figured by the herbalists, that the pointed-headed early cabbages appeared only at a comparatively recent date, and certain resemblances between Pe-tsai and the long-headed cabbages, it is not an impossible suggestion that these cabbage-forms appeared as the effect of cross-fertilization with the Chinese cabbage. But, until the cabbage family has received more study in its varieties, and the results of hybridization are better understood, no certain conclusion can be reached. It is, however, certain that occasional rare sports, or variables, from the seed of our early, long-headed cabbages show the heavy veining and the limb of the leaf extending down the stalk, suggesting strongly the Chinese type. At present, however, views as to the origin of various types of cabbage must be considered as largely speculative."

Brassica cretica: "Mediterranean regions. The young shoots were formerly used in Greece."

Brassica juncea: "The plant is extensively cultivated throughout India, central Africa and generally in warm countries. It is largely grown in south Russia and in the steppes northeast of the Caspian Sea. In 1871-72, British India exported 1418 tons of seed. The oil is used in Russia in the place of olive oil. The powdered seeds furnish a medicinal and culinary mustard."

Brassica nigra: "This is the mustard of the ancients and is cultivated in Alsace, Bohemia, Italy, Holland and England. The plant is found wild in most parts of Europe and has become naturalized in the United States. According to the belief of the ancients, it was first introduced from Egypt and was made known to mankind by Aesculapius, the god of medicine, and Ceres the goddess of seeds. Mustard is mentioned by Pythagoras and was employed in medicine by Hippocrates, 480 B. C. Pliny says the plant grew in Italy without sowing. The ancients ate the young plants as a spinach and used the seeds for supplying mustard.

Black mustard is described as a garden plant by Albertus Magnus in the thirteenth century and is mentioned by the botanists of the sixteenth century. It is, however, more grown as a field crop for its seed, from which the mustard of commerce is derived, yet finds place also as a salad plant. Two varieties are described, the Black Mustard of Sicily and the Large-seeded Black. This mustard was in American gardens in 1806 or earlier. The young plants are now eaten as a salad, the same as are those of B. alba and the seeds now furnish the greater portion of our mustard."

Brassica oleracea acephala: "The chief characteristics of this species of Brassica are that the plants are open, not heading like the cabbages, nor producing eatable flowers like the cauliflowers and broccoli. The species has every appearance of being one of the early removes from the original species and is cultivated in many varieties known as kale, greens, sprouts, curlico, with also some distinguishing prefixes as Buda kale, German greens. Some are grown as ornamental plants, being variously curled, laciniated and of beautiful colors. In 1661, Ray journeyed into Scotland and says of the people that "they use much pottage made of coal-wort which they call keal." It is probable that this was the form of cabbage known to the ancients.

The kales represent an extremely variable class of vegetable and have been under cultivation from a most remote period. What the varieties of cabbage were that were known to the ancient Greeks it seems impossible to determine in all cases, but we can hardly question but that some of them belonged to the kales. Many varieties were known to the Romans. Cato, who lived about 201 B. C., describes the Brassica as: the levis, large broad-leaves, large-stalked; the crispa or apiacan; the lenis, small-stalked, tender, but rather sharp-tasting. Pliny, in the first century, describes the Cumana, with sessile leaf and open head; the Aricinum, not excelled in height, the leaves numerous and thick; the Pompeianum, tall, the stalk thin at the base, thickening along the leaves; the brutiana, with very large leaves, thin stalk, sharp savored; the sabellica, admired for its curled leaves, whose thickness exceeds that of the stalk, of very sweet savor; the Lacuturres, very large headed, innumerable leaves, the head round, the leaves fleshy; the Tritianom, often a foot in diameter and late in going to seed. The first American mention of coleworts is by Sprigley, 1669, for Virginia but this class of the cabbage tribe is probably the one mentioned by Benzoni as growing in Hayti in 1565. In 1806, McMahon recommends for American gardens the green and the brown Aypres and mentions the Red and Thick-leaved Curled, the Siberian, the Scotch and especially recommends Jerusalem kale.

The form of kale known in France as the chevalier seems to have been the longest known and we may surmise that its names of chou caulier and caulet have reference to the period when the word caulis, a stalk, had a generic meaning applying to the cabbage race in general. We may hence surmise that this was the common form in ancient times, in like manner as coles or coleworts in more modern times imply the cultivation of kales. This word coles or caulis is used in the generic sense, for illustration, by Cato, 200 years B. C.; by Columella the first century A. D.; by Palladius in the third; by Vegetius in the fourth century A. D.; and Albertus Magnus in the thirteenth. This race of chevaliers may be quite reasonably supposed to be the levis of Cato, sometimes called caulodes."

Brassica oleracea botrytis cymosa (Brokkoli): "The differences between the most highly improved varieties of the broccoli and the cauliflower are very slight; in the less changed forms they become great. Hence two races can be defined, the sprouting broccolis and the cauliflower broccolis. The growth of the broccoli is far more prolonged than that of the cauliflower, and in the European countries it bears its heads the year following that in which it is sown. It is this circumstance that leads us to suspect that the Romans knew the plant and described it under the name cyma—"Cyma a prima sectione praestat proximo vere." "Ex omnibus brassicae generibus suavissima est cyma," says Pliny. He also uses the word cyma for the seed stalk which rises from the heading cabbage. These excerpts indicate the sprouting broccoli, and the addition of the word cyma then, as exists in Italy now, with the word broccoli is used for a secondary meaning, for the tender shoots which at the close of winter are emitted by various kinds of cabbages and turnips preparing to flower.

It is certainly very curious that the early botanists did not describe or figure broccoli. The omission is only explainable under the supposition that it was confounded with the cauliflower, just as Linnaeus brought the cauliflower and the broccoli into one botanical variety. The first notice of broccoli is quoted from Miller's Dictionary, edition of 1724, in which he says it was a stranger in England until within these five years and was called "sprout colli-flower," or Italian asparagus. In 1729, Switzer says there are several kinds that he has had growing in his garden near London these two years: "that with small, whitish-yellow flowers like the cauliflower; others like the common sprouts and flowers of a colewort; a third with purple flowers; all of which come mixed together, none of them being as yet (at least that I know of) ever sav'd separate." In 1778, Mawe, names the Early Purple, Late Purple, White or Cauliflower-broccoli and the Black. In 1806, McMahon mentions the Roman or Purple, the Neapolitan or White, the Green and the Black. In 1821, Thorbum names the Cape, the White and the Purple, and, in 1828, in his seed list, mentions the Early White, Early Purple, the Large Purple Cape and the White Cape or Cauliflower-broccoli. The first and third kind of Switzer, 1729, are doubtless the heading broccoli, while the second is probably the sprouting form. These came from Italy and as the seed came mixed, we may assume that varietal distinctions had not as yet become recognized, and that hence all the types of the broccoli now grown have originated from Italy. It is interesting to note, however, that at the Cirencester Agricultural College, about 1860, sorts of broccoli were produced, with other variables, from the seed of wild cabbage.

Vilmorin says: "The sprouting or asparagus broccoli, represents the first form exhibited by the new vegetable when it ceased to be the earliest cabbage and was grown with an especial view to its shoots; after this, by continued selection and successive improvements, varieties were obtained which produced a compact, white head, and some of these varieties were still further improved into kinds which are sufficiently early to commence and complete their entire growth in the course of the same year; these last named kinds are now known as cauliflowers."

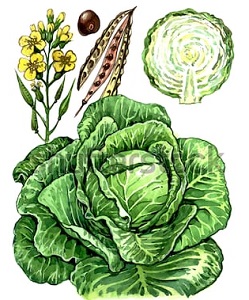

Brassica oleracea capita (Weißkohl): "Few plants exhibit so many forms in its variations from the original type as cabbage. No kitchen garden in Europe or America is without it and it is distributed over the greater part of Asia and, in fact, over most of the world. The original plant occurs wild at the present day on the steep, chalk rocks of the sea province of England, on the coast of Denmark and northwestern France and, Lindley says, from Greece to Great Britain in numerous localities. At Dover, England, wild cabbage varies considerably in its foliage and general appearance and in its wild state is used as a culinary vegetable and is of excellent flavor. This wild cabbage is undoubtedly the original of our cultivated varieties, as experiments at the garden of the Royal Agricultural College and at irencester resulted in the production of sorts of broccoli, cabbages and greens from wild plants gathered from rocks overhanging the sea in Wales. Lindley groups the leading variations as follows: If the race is vigorous, long jointed and has little tendency to turn its leaves inwards, it forms what are called open cabbages (the kales); if the growth is stunted, the joints short and the leaves inclined to turn inwards, it becomes the heart cabbages; if both these tendencies give way to a preternatural formation of flowers, the cauliflowers are the result. If the stems swell out into a globular form, we have the turnip-rooted cabbages. Other species of Brassica, very nearly allied to B. oleracea Linn., such as B. balearica Richl., B. insularis Moris, and B. cretica Lam., belong to the Mediterranean flora and some botanists suggest that some of these species, likewise introduced into the gardens and established as cultivated plants, may have mixed with each other and thus have assisted in, giving rise to some of the many races cultivated at the present day.

The ancient Greeks held cabbage in high esteem and their fables deduce its origin from the father of their gods; for, they inform us that Jupiter, laboring to explain two oracles which contradicted each other, perspired and from this divine perspiration the colewort sprung. Dioscorides mentions two kinds of coleworts, the cultivated and the wild. Theophrastus names the curled cole, the swath cole and the wild cole. The Egyptians are said to have worshipped cabbage, and the Greeks and Romans ascribed to it the happy quality of preserving from drunkenness. Pliny mentions it. Cato describes one kind as smooth, great, broadleaved, with a big stalk, the second ruffed, the third with little stalks, tender and very much biting. Regnier says cabbages were cultivated by the ancient Celts.

Cabbage is one of the most generally cultivated of the vegetables of temperate climates. It grows in Sweden as far north as 67° to 68°. The introduction of cabbage into European gardens is usually ascribed to the Romans, but Olivier de Serres says the art of making them head was unknown in France in the ninth century. Disraeli says that Sir Anthony Ashley of Dorsetshire first planted cabbages in England, and a cabbage at his feet appears on his monument; before his time they were brought from Holland. Cabbage is said to have been scarcely known in Scotland until the time of the Commonwealth, 1649, when it was carried there by some of Cromwell's soldiers. Cabbage was introduced into America at an early period. In 1540, Cartier in his third voyage to Canada, sowed cabbages. Cabbages are mentioned by Benzoni as rowing in Hayti in 1556; by Shrigley, in Virginia in 1669; but are not mentioned especially by Jefferson in 1781. Romans found them in Florida in 1775 and even cultivated by the Choctaw Indians. They were seen by Nieuhoff in Brazil in 1647. In 1779, cabbages are mentioned among the Indian crops about Geneva, New York, destroyed by Gen. Sullivan in his expedition of reprisal. In 1806, McMahon mentions for American gardens seven early and six late sorts. In 1828, Thorbum offered 18 varieties in his seed catalog and in 1881, 19. In 1869, Gregory tested 60 named varieties in his experimental garden and in 1875 Landreth tested 51.

The headed cabbage in its perfection of growth and its multitude of varieties, bears every evidence of being of ancient origin. It does not appear, however, to have been known to Dioscorides, or to Theophrastus or Cato, but a few centuries later the presence of cabbage is indicated by Columella and Pliny, who, of his variety, speaks of the head being sometimes a foot in diameter and going to seed the latest of all the sorts known to him. The descriptions are, however, obscure, and we may well believe that if the hard-headed varieties now known had been seen in Rome at this time they would have received mention. Olivier de Serres says: "White cabbages came from the north, and the art of making them head was unknown in the time of Charlemagne." Albertus Magnus, who lived in the twelfth century, seems to refer to a headed cabbage in his Caputium, but there is no description. The first unmistakable reference to cabbage is by Ruellius, 1536, who calls them capucos coles, or cabutos and describes the head as globular and often very large, even a foot and a half in diameter. Yet the word cabaches and caboches, used in England in the fourteenth century, indicates cabbage was then known and was distinguished from coles. Ruellius, also, describes a loose-headed form called romanos, and this name and description, when we consider the difficulty of heading cabbages in a warm climate, would lead us to believe that the Roman varieties were not our present solid-heading type but loose-headed and perhaps of the savoy class.

Our present cabbages are divided by De Candolle into five types or races: the flat-headed, the round-headed, the egg-shaped, the elliptic and the conical. Within each class are many sub-varieties. In Vilmorin's Les Plantes Potageres, 1883, 57 kinds are described, and others are mentioned by name. In the Report of the New York Agricultural Experiment Station for 1886, 70 varieties are described, excluding synonyms. In both cases the savoys are treated as a separate class and are not included."

Brassica oleracea caulo-rapa communis (Kohlrabi): "This is a dwarf-growing plant with the stem swelled out so as to resemble a turnip above ground. There is no certain identification of this race in ancient writings. The bunidia of Pliny seems rather to be the rutabaga, as he says it is between a radish and a rape. The gorgylis of Theophrastus and Galen seems also to be the rutabaga, for Galen says the root contained within the earth is hard unless cooked. In 1554, Matthiolus speaks of the kohl-rabi as having lately come into Italy. Between 1573 and 1575, Rauwolf saw it in the gardens of Tripoli and Aleppo. Lobel, 1570, Camerarius, 1586, Dalechamp, 1587, and other of the older botanists figure or describe it as under European culture. Kohl-rabi, in the view of some writers, is a cross between cabbage and rape, and many of the names applied to it convey this idea. This view is probably a mistaken one, as the plant in its sportings under culture tends to the form of the Marrow cabbage, from which it is probably a derivation. In 1884, two kohl-rabi plants were growing in pots in the greenhouse at the New York Agricultural Experiment Station; one of these extended itself until it became a Marrow cabbage and when planted out in the spring attained its growth as a Marrow cabbage. This idea of its origin finds countenance in the figures of the older botanists; thus, Camerarius, 1586, figures a plant as a kohl-rabi which in all essential points resembles a Marrow cabbage, tapering from a small stem into a long kohl-rabi, with a flat top like the Marrow cabbage. The figures given by Lobel, 1591, Dodonaeus, 1616, and Bodaeus, 1644, when compared with Camerarius' figure, suggest the Marrow cabbage. A long, highly improved form, not now under culture, is figured by Gerarde, 1597, J. Bauhin, 1651, and Chabraeus, 1677, and the modern form is given by Gerarde and by Matthiolus, 1598. A very unimproved form, out of harmony with the other figures, is given by Dalechamp, 1587, and Castor Durante, 1617."

Brassica sinapistrum (Ackersenf): "This is an European plant now occurring as a weed in cultivated fields in America. In seasons of scarcity, in the Hebrides, the soft stems and leaves are boiled in milk and eaten. It is so employed in Sweden and Ireland. Its seeds form a good substitute for mustard."

Bridelia retusa: "A tree of eastern Asia. The fruit is sweetish and eatable."

Brodiaea grandiflora: "Northwestern America. Its fruit is eaten by the Indians. In France, it is grown in the flower garden."

Brosimum alicastrum: "American tropics. The fruit, boiled with salt-fish, pork, beef or pickle, has frequently been the support of the negro and poorer sorts of white people in times of scarcity and has proved a wholesome and not unpleasant food."

Brosimum galactodendron: "Guiana; the polo de vaca, arbol de lecke, or cow-tree of Venezuela. Humboldt says "On the barren flank of a rock grows a tree with coriaceous and dry leaves. Its large, woody roots can scarcely penetrate into the stone. For several months of the year not a single shower moistens its foliage. Its branches appear dead and dried; but when the trunk is pierced there flows from it a sweet and nourishing milk. It is at the rising of the sun that this vegetable fountain is most abundant. The negroes and natives are then seen hastening from all quarters, furnished with large bowls to receive the milk which grows yellow and thickens at its surface. Some empty their bowls under the tree itself, others carry the juice home to their children." This tree seems to have been noticed first by Laet in 1633, in the province of Camana. The plant, according to Desvaux, is one of the polo de vaca or cow-trees of South America. From incisions in the bark, milky sap is procured, which is drunk by the inhabitants as a milk. Its use is accompanied by a sensation of astringency in the lips and palate. This cow-tree is grown in Ceylon and India, for Brandis says it yields large quantities of thick, gluey milk without any acridity, that it is drunk extensively, and that it is very wholesome and nourishing."

Broussonetia papyrifera: "A tree of the islands of the Pacific, China and Japan. It is cultivated for the inner bark which is used for making a paper as well as textile fabrics. The fleshy part of the compound fruit is saccharine and edible."

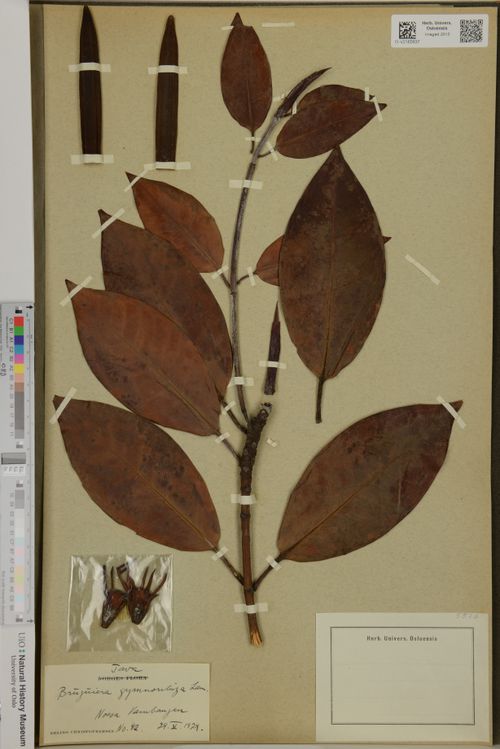

Bruguiera gymnorrhiza: "Muddy tropical shores from Hindustan to the Samoan Islands. Its fruit, leaves and bark are eaten by the natives in the Malayan Archipelago."

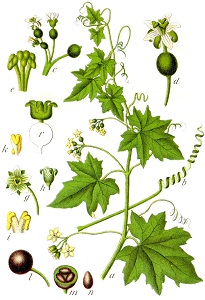

Bryonia alba (Schwarz-Zaunrübe): "West Mediterranean countries. Loudon says the young shoots are edible."

Bryonia dioica (Rot-Zaunrübe): "Europe and adjoining Asia. Loudon says the young shoots of red bryony are edible. Masters says that the plant has a fetid odor and possesses acrid, emetic and pungent properties."

Buchanania lancifolia: "East Indies and Burma. The tender, unripe fruit is eaten by the natives in their curries."

Bumelia lanuginosa: "North America. This is a low bush of southern United States which, according to Nuttall, bears an edible fruit as large as a small date."

Bumelia reclinata: "Southwestern United States. In California, Torrey says the fruit is sweet and edible and nearly three-quarters of an inch long."

Bunias erucago (Zackenschote): "Mediterranean countries. In Italy, Unger says this species serves as a salad for the poor."

Bunias orientalis (Orient-Zackenschötchen): "Eastern Europe and Asia Minor. This plant is called dikaia retka on the Lower Volga. Its stems are eaten raw. This rocket was cultivated in 1739 by Philip Miller in the Botanic Garden of Chelsea and was first introduced into field culture in England as a forage plant, by Arthur Young. The young leaves are recommended by Vilmorin either as a salad or boiled."

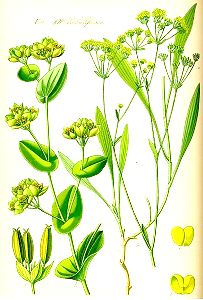

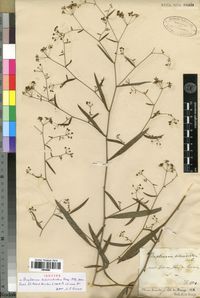

Bupleurum falcatum (Sichel-Hasenohr): "Europe, Orient, Northern Asia and Himalayan region. The leaves are used for food in China and Japan."

Bupleurum octoradiatum: "Northern China. In China, the tender shoots of this apparently foreign plant are edible."

Bupleurum rotundifolium (Durchwachs-Hasenohr): "Europe, Caucasus region and Persia. “Hippocrates hath commended it in meats for salads and potherbs."

Burasaia madagascariensis: "Madagascar. This plant has edible fruit."

Bursera gummifera: "American tropics. An infusion of the leaves is occasionally used as a domestic substitute for tea."

Bursera icicariba: "Brazil. The tree is said to have edible, aromatic fruit. It yields the elemi of Brazil."

Bursera javanica: "Java. This plant is the tingulong of the Javanese, who eat the leaves and fruit."

Butomus umbellatus: "Europe and adjoining Asia. Unger says, in Norway, the rhizomes serve as material for a bread. Johns says, in the north of Asia, the root is roasted and eaten. Lindley says the rhizomes are acrid and bitter, as well as the seeds but are eaten among the savages. In France, it is grown in flower gardens as an aquatic."

Butyrospermum parkii: "Tropical west Africa. Shea, or galam, butter is obtained from the kernel of the fruit and serves the natives as a substitute for butter. This butter is highly commended by Park. The tree is called meepampa in equatorial Africa."

Buxus sempervirens (Buchsbaum): "Europe, Orient and temperate Asia. In France and some other parts of the continent, the leaves of the box have been. used as a substitute for hops in beer, but Johnson says they cannot be wholesome and would probably prove very injurious."

Byrsonima crassifolia: "A small tree of New Granada and Panama. The small, acid berries are eaten."

Byrsonima spicata: "Tropical America. The yellow, acid berries are good eating but astringent."